The desire to attain an altered state of consciousness is embedded deep in humanity. Something to take the edge off life, to allow us to forget our worries and be merry for a while, is a common desire. That something for many is alcohol, its popularity in part due to it’s legal and socially accepted status in the UK. Alongside this popular legal high there are a growing number of illicit highs that people turn to get their kicks, or seek solace.

The human desire for altered states is something that we share with other primates. Black Lemurs in Madagascar seek out millipedes and enter a drooling trance like state from the toxins released by millipedes when they are enthusiastically chewed on, but not eaten, by the Lemurs.

The “drunken monkey” hypothesis put forward by evolutionary physiologist Robert Dudley suggests some fruit eating primate species intentionally seek out ripe fruits (containing naturally fermented alcohol) and are generating about 90% of their calorific output from them.

Vervet monkeys in the Caribbean, who learnt to steal booze from sleeping tourists and local bars, developed specific tastes, some preferring their alcohol diluted in fruit juice, some preferring it neat, and others subject to binge drinking themselves into unconsciousness.

So it’s possible this propensity for seeking out mind altering substances may have developed alongside our evolutionary journey to becoming homo sapiens. Drug use by humans certainly stretches far back into our prehistory, with evidence pointing to the use of marijuana and opium poppies in Bronze Age (3,300 BC to 1200 BC) sites in Turkmenistan, and the use of hallucinogenic plants in Peru as far back as 8,600 BC.

In opposition to this deep-seated desire to attain altered states is a puritan streak in humanity, that regards pleasure as sinful and decadent, which was particularly strong in the United States political class who, undeterred by the myriad failures of alcohol prohibition across the States in the 1920’s, decided to stamp down on all other drugs instead and encouraged countries across the world to join a modern-day crusade: the war on drugs.

In 1971 President Richard Nixon, besieged by criticism from the anti-war left and black people calling for civil rights, declared drug abuse “public enemy number one”, and his war on drugs, funded by US dollars in countries across the world, became a common description of the global efforts to control and prohibit drug use.

War on drugs

“Many people have said the war on drugs, and the war on drugs in America, is a race war. It’s not a war on drugs”, says Rob Ralphs, professor of Criminology and Social Policy at Manchester Metropolitan University. Ralphs was born and bred in Manchester, one of the most culturally diverse cities in the UK, , and has lived through and investigated the effects of drug use and prohibition polices on the people living in this city, and the whole population of the UK. His work covers the whole gamut of drug use, with a particular focus on the rise of synthetic cannabinoids in recent years.

One of the many injustices concerning the policies that drive the war on drugs is that the casualties are more likely to be amongst ethnic minorities or disadvantaged groups in society. Although studies have shown that black and white people in the UK have similar levels of drug use, black people were 8.3 times more likely to be stopped and searched for drugs than white people in 2019/20.

Once arrested black people are more likely to be prosecuted than white people by a factor of eight. And when it comes to cannabis black people were convicted at 11.8, and Asian people at 2.4, times the rate of white people. Black people make up just over 3% of the population in the UK, yet they made up 26% of all cannabis possession convictions in 2017.

Although the US is well known for its huge prison population, with black people overrepresented within it, black people in the UK are proportionally more likely to be in prison than those in the US, with a study conducted in 2017 by MP David Lammy showing that black people in the UK are four times more likely (in the US it’s around three times) to be incarcerated, than would be expected given their proportion of the population total.

Being involved with the criminal justice system at a young age can have severe repercussions for the rest of the persons life, with re-offending rates high for ex-prisoners and they also face severe difficulties when trying to get suitable employment..

Ralph says to counter this problem faced by ethnic minorities due to “over policing and over representation in the criminal justice system, then you need to change drug laws because you have so much of that kind of stop and search suspicion of cannabis possession, or links to low-level drug dealing. It’s important that we do change prohibition policies and policing policies around drug use if we want to have that wider change.”

Life and death on drugs

Current drug policy disproportionately affects ethnic minorities and disadvantaged groups, but it also affects drug takers of any stripe and since milestone legislation to control drugs was introduced in 1971 over three million criminal records have been generated across the UK for drugs offences. In England and Wales, 16% of the total prison population were imprisoned due to drug offences in 2020. And more than 80% of all drug offences have been for minor possession charges, since 2010.

When it comes to deaths related to drug use, the statistics for the UK are particularly shocking. Data collected across Europe by the EMCDDA, show that in 2020 there were 3284 overdose deaths in the UK, the next highest total for that year comes from Turkey with 657.

The war on drugs has failed to stem the rising number of deaths due to drug misuse across England, with the graph below showing an increasing trend of drug deaths across the country between 1993 and 2019. The increase is largely due to a sharp rise in heroin linked deaths during these years; over the same time period across Greater Manchester deaths due to drug misuse have increased from 180 to 268. The trend continues to rise, with the latest figures for 2021 showing that there were 2830 drug misuse deaths across England.

Number of Drug misuse poisonings in England between 1993 and 2019

Legislation underpinning the drugs war

The casualties to life, and life chances, continue to grow in the war on drugs, and a similar losing story is found when you look at any of the statistics concerning drug use and the attempts to control it with prohibitive legislation.

Since the primary legislation to prohibit drugs in the UK was introduced in 1971, the number of people using heroin in England by 2019 has increased 25-fold, while over the same time frame cannabis use across England and Wales has increased five-fold. There has also been a trend for rising potency and availability of illicit drugs, alongside stable or even falling prices.

Prior to Nixon’s declaration of war on drugs the US and UK were prime movers in the introduction of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs 1961, an international treaty that controls the production, supply, trade and use of specific narcotic drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and cannabis, which has 186 countries signed up to it. The Single Convention, overseen by the UN Office on Drugs Crime, acts as a guide for countries signed up to enact their own legislation that complies with it.

The primary UK legislation to prohibit drugs which fits under the Single Convention, and other international treaties supplementing it, is the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (MDA). Since its introduction just over 50 years ago it has never been subject to a formal review or evaluation.

The Transform Drug Policy Foundation called this “50 years of failure” in a campaign they ran to highlight the inbuilt inequities in the MDA, which featured 65 UK MPs and peers who supported a review of the MDA. This included Labour’s Jeff Smith MP for Manchester, Withington, who spoke in parliament on 17 June saying that even government reports showed “no relationship between tougher punitive sanctions on drug possession, and the level of drug use in the country.”

Ester Kincova, public affairs and policy manager at Transform, says that the lack of meaningful evaluation of the Misuse of Drugs Act over the last five decades is “just insanity, and we’ve been highlighting that actually under all metrics, it’s pretty much failed from use going up exponentially in the last 50 years to drug related deaths to availability on the market. The strength of the illegal drug market, which is now by the government’s own estimates, about £9 billion a year.”

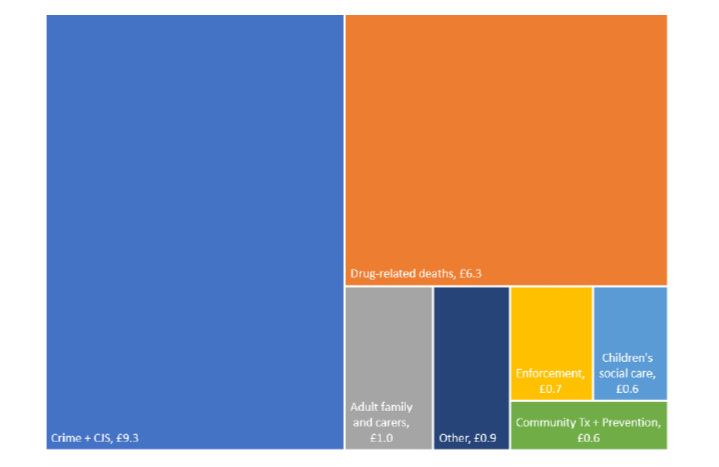

Dame Carol Black’s report released in 2020 listed the illicit drugs market at £9.4 billion a year in England and Wales, and stated that the drugs “market had become much more violent”. Organised crime is understandably keen to get a bigger slice of this growing pie. The overall cost to society was estimated at £19 billion a year, when the health harms, costs of crime and wider impacts on society were taken into consideration.

Components of drug related costs (£bns)

Sharing Ralph’s concerns around discriminatory use of drug laws, Kincova says the “current drug policy we have is the sharpest tool in the box for the police to persecute ethnic minority groups, and it’s most starkly demonstrated in stop and search statistics.” Kincova believes that the drugs legislation is not in itself inherently racist, but its use has allowed “for policing to perpetuate systemic racism for this last five decades.”

Drug use demonisation

The stigmatisation of drug use by government policy and sensationalist media coverage in the UK has led to the “othering” of drug users and a widely held narrative deeply embedded in society of the evil, uncaring, selfish, dangerous junkie; which legitimises society’s treatment of drug users and limits the potential for debate on the issue.

This othering of drug users was taken to the extremes by President Rodrigo Duterte’s brutal battle fought in the name of the war on drugs in the Philippines, where he promised to get rid of the “filth” from the streets. Human Rights Watch estimated that police and “unidentified gunmen” killed 7,000 suspected drug dealers and users during anti-drug operations in the first year of Duterte’s office, from 2016-17. The persecution and murder of drug users and dealers was criticised as being a war on the poor due to the abject poverty of many of those killed or arrested, and the International Criminal Court is currently investigating ex-president Duterte’s involvement with the “death squads” carrying out the killings.

The stigma and stereotypes around drug use and their effects on individuals and society is a primary concern for Dr Rebecca Askew a senior lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Manchester Metropolitan University. Askew’s research explores “the reasons that people use drugs, that go beyond this idea that we’re either recreational drug takers who do it occasionally, and it’s just not a problem. Or we are addicted to some sort of substance, usually heroin, alcohol doesn’t get talked about that much, even though most of us are probably dependent on it in some way.

“We’ve got these kind of binaries in the way that we speak about people who use drugs, and my work is really trying to challenge that we have these strict binaries because I just don’t think it’s useful to understand drug use in that way.”

Askews research has taken in the drug use experience of Generation X, the sort of people that are now in their late 40’s and early 50’s, who might have been seen bopping about in the Hacienda.

During this research she has interviewed over 150 people, who are still taking drugs, but are generally seen as conforming citizens, not criminals and for many their drug use is not problematic, it is “just part of their lives. It might be that they smoke a joint every night, or is still having a glass of wine a night. It might be that you’re still taking E’s. It might be coke, every month, every week.”

Drug Policy Voices is one of Askew’s research projects, with an associated podcast, that aims to broaden the debate around drug policy reform by bringing in the voices of those who use drugs, which are often missing from more formal debates and reports into drug use. And when it comes to reforming drug policy such as the Misuse of Drugs Act, Askew’s research has emphasised that “the first positive move and change from my perspective is reducing that stigma and judgement on people who are taking drugs and involving them in the conversation.”

The media is “very powerful” at promoting narratives around “who the good guys are and who the bad guys are” and use stigmatising language such as “spice heads” or “scag heads”, Askew says and adds:

“Drug Policy Voices is trying to educate people and improve public knowledge, because as soon as you connect somebody to someone’s experiences of drug use, they become humanised. What some of the mainstream media have done is dehumanise people who take drugs, for too many years.

“And we have built up this othered and alien population, the outsiders that we want to try and avoid any contact with. I think that’s a huge disservice and has caused huge stigmatisation to people.”

Moralisation is the major driver for the Misuse of Drug Act, Askew argues:

“We could look at like lots of different things from either psychology, and from law and political positions of how, what do we morally feel about drugs? Because that’s what it boils down to, the Misuse of Drugs Act is moralised.

“It’s that some drugs are OK and some drugs aren’t. We have known for many years that this is not evidence based on the dangerousness of drugs. Because if it was then alcohol would be banned and so would tobacco.”

A war targeting the vulnerable

The Black report documents the prevalence of problematic drug use in those who are homeless, with over 60% of people rough sleeping in need of drug or alcohol treatment, and 40% having drug related issues. Rough sleepers also generally have poorer health with respiratory and other illnesses more common when compared to the general population. This may be a contributing factor to drug poisoning deaths increasing by 55% in 2018, in the homeless population, contributing to two fifths of all deaths.

The decade of austerity led to drug and alcohol services being cut, as they were seen as “nice to haves” by local authorities having to balance their budgets, with the Black report stating that some local authorities had reduced treatment expenditure by up to 40%. Those cuts have been particularly hard on outreach services, drop-in sessions and flexible working hours for outreach workers, which are elements of the service critical to rough sleepers with chaotic lifestyles.

Ralphs estimates there has been on average around a 25% cut to local authority drug services across the UK over the last decade, with larger cuts to youth services, but he believes Manchester city council has protected their drug services to a better extent than some other local authorities. The Black report states: “Many key indicators (deaths, unmet need, recovery rates) are going in the wrong direction and there is significant variation in both local spend in relation to need… but outcomes tend to be worse in the north of the country…”

While carrying out research for Manchester city council into new psychoactive substances such as “Spice” in 2016, Ralphs said the report produced “ended up being dominated by homeless supported accommodation sector saying, “we’ve got massive problems with spice.”

That initial report led to Ralphs producing an annual research survey, unique to the UK, called GM Trends, that looks at emerging drug use trends across the region, which he says needs “to look at prisons because quite often out of necessity and innovation new drug trends emerge in prison. And then it’s quite often the same population who will be homeless, living on the streets in and out of prison and living in hostels.”

At least a third of the people in UK prisons are locked up due to crimes related to drug use, with most in for acquisitive crimes such as theft, burglary, and robbery. Spice use in prison is popular as an alternative to cannabis as it doesn’t show up in drug tests as readily. The Black report also shows drug treatment in prison failing the inmates, with around 40% of opiate users and 33% of non-opiate users in prison treatment for less than two months, with a majority only receiving two weeks treatment or less. The US the National Institute on Drug Abuse says that “for residential or outpatient treatment, participation for less than 90 days is of limited effectiveness”. When prisoners are released in the UK they also face issues with only a third of them referred to treatment in the community receiving it within three weeks.

This matters because treatment does work. The Black report reveals opiate users reduce their offending by nearly 40% when they successfully complete treatment, and similar reductions are seen for opiate users that maintain contact with treatment. Ralphs says the “Dame Carol Black report into drugs was the most significant report into drugs for the last 20 years or so, and pretty much the [government] drug strategies followed quite closely its recommendations”.

The government’s response to the Black report was the launch of a strategy outlined in a policy paper released in December 2021, “From harm to hope: A 10-year drugs plan to cut crime and save lives”. The strategy aims to break the drugs supply chain, create a world class treatment and recovery system, and achieve a generational shift in the demand for drugs in order to “reduce drug-related crime, death, harm and overall drug use.”

An additional £780 million has been promised to drug services over the next three years, which will go some way to replacing the funding lost over a decade of austerity. In 2018 the BBC reported that there had been a £162 million cut to drug and alcohol treatment services across England in just four years, which occurred alongside a 7% fall in people accessing services and an increase in drug related deaths. The Black report raises the issue of the diminished state of current drug services due to a decade of austerity, with a loss of professional staff being a key issue, so a significant amount of any new resources will be needed to bring services to a level they were previously at.

The government strategy is no radical departure from the war on drugs, it is another push on the same front, although it is trying to limit the “collateral damage” to drug users’ health and lives. Ralphs says much of the strategy is covering old ground:

“Things always kind of come back around again. What was announced in the drugs strategy wasn’t really much different to the 2000s, when it was all about the drugs intervention programme.”

The latest government drugs strategy has overtones of the failed push against insurgents in Afghanistan, where US and British military forces were convinced the situation could be changed by doing more of the same. More boots, bombs and bullets did not win that war, and instead led to the ignominious departure of western military forces from Afghanistan, which ironically for this story is the largest producer and exporter of opium in the world.

The myth of the many headed serpent Hydra, who would regrow two heads for every one chopped off, is a common analogy applied to the war on drugs and why it is unwinnable. No matter how many drug dealers’, large or small, heads you cut off (literally in Duterte’s case) there will always be others, often from disadvantaged backgrounds, to replace them due to the incredible profits available to those taking on the role of dealing in illicit drugs when market demand is, and has always been, so high.

There are alternatives to the war on drugs and it’s prohibitionist policies. One that could be viewed as a ceasefire or a humanitarian corridor leading drug users away from the brutalisation inherent in the criminal justice system are drug diversion schemes, which are already being successfully used in certain areas of the UK to divert drug users towards drug services and away from prison cells.

Change is needed for peace to break out in this war, and that change is already happening in countries across the world laying down their arms, and embracing decriminalisation and legalisation policies to manage drug use in society. The next segment of this story will look at these alternatives, to the current war without end prohibition policies, and their potential to radically change how we do drugs in the UK.

For part two of this story – click here

For a wealth of information on drug policy reform from Transform – click here

For Dame Carol Black’s Independent Review of Drugs – click here

Sign up to The Meteor mailing list – click here

The Meteor is a media co-operative on a mission to democratise the media in Manchester. To find out more – click here

This story is part of the Creating Radical Change series

Featured image: Wikipedia Commons, Pixnio

Leave a Reply