I’m in a lecture theatre at the University of Manchester, on a stifling summer’s day in 2017, with a grazing herd of Anthony Burgess geeks. It’s the last lap of a three-day conference to mark the writer’s centenary – we’ve sat through talks on everything from Burgess’s Blackpool to A Clockwork Orange in French – and now the poet John McAuliffe is at the lectern reeling off a list of noted writers to have emerged from the city.

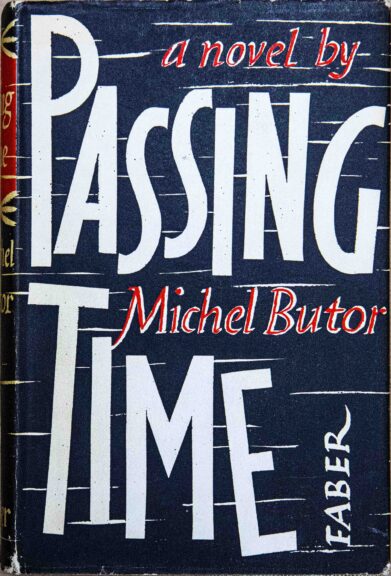

Elizabeth Gaskell…Howard Spring…Howard Jacobson…in among the famous names there’s an unfamiliar one, Michel Butor, and an unassuming-sounding novel, Passing Time. I’ve never heard of these, I don’t think. There’s something about the 1950s and being driven mad by the city and a literary dialogue with the German writer, W.G. Sebald…did I read something about this in the Manchester Review once?

I go home, I google. And that’s when I stumble across a Passing Time blog written by a University of Sheffield PhD student, Cath Annabel. “About fifteen years ago I started reading a 1950s French novel…nothing remarkable there, except that I’m still reading it.” The site is brimming with discussion about an imaginary town called “Bleston”, which is apparently based on Manchester. There’s an imaginary map, talk of labyrinths, minotaurs, and madness.

Then there’s the Sebald link. Like Butor before him, I learn, the German came to teach at the University of Manchester in the 1960s, and appears to have read Passing Time soon after his arrival. “The acute culture shock and sense of isolation Max suffered during his first term could not have been helped by his Baudelairean / Benjaminian flâneries through scenes of slum clearance and urban decay…or by his reading of Butor’s novel,” records scholar Richard Sheppard of the groundbreaking author. I’m aware that since his death in 2001 Sebald has been hailed as one of the greatest writers never to win the Nobel Prize. His reputation continues to soar. He wrote poetry addressing fictional Bleston, establishing a bridge between the two writers’ respective worlds. Two markedly unorthodox worlds, I should say.

With some difficulty I get hold of a copy of Passing Time – an ugly Jupiter Press edition from the 60s. The book is long out of print. Even in translation the prose is conspicuously, lyrically poetic. It begins: “Suddenly there were a lot of lights…” A Frenchman named Revel pulls in at the train station in a rainswept northern town to take up a clerk’s position. Very quickly he begins to feel the town is psychologically undermining him. He meets two sisters with whom he in turn falls in love, but loses each to other suitors. Chancing on a mystery novel called The Bleston Murder, he encounters its author, one JC Hamilton. But when the writer is almost killed in a hit-and-run incident Revel becomes obsessed by the idea that all these things are somehow related. Slowly, his determination to join the dots between them starts to unravel his mind, so he begins belatedly to keep a diary in the bid to make sense of everything.

Increasingly, he addresses the town itself. “It might seem at first glance that you are made up only of stones and men, and that animals have no share in your being, but if one considers the caged beasts in the Pleasance Gardens Zoo [for which we can read ‘50s Belle Vue] the last remaining cart horses and the processions bound for the slaughterhouse in the 11th district, the innumerable cats and all the vermin, one is forcibly made aware that these too have become an organic part of your system, and that alive or dead, spectacular or parasitic, meat or carrion, they incarnate certain of your powers.”

Be prepared, what unfolds is no easy read. It’s like swimming into the undertow of madness itself. What gives the novel its effect is its structure: the diary begun seven months after-the-fact as a breadcrumb trail through the labyrinth of Revel’s mind in the attempt to keep hold of his sanity. It allows Butor the author to range backwards and forwards in time, continually circling, returning to and alighting from the same infernal series of events in the attempt to prise some significance from their randomness – thus indulging and subverting the author’s great passion for rich Proustian prose.

“It’s like a fugue,” Cath Annabel tells me, when I track her down in Sheffield later that year. “You introduce a voice but it’s complicated by further voices coming in…Butor said he deliberately structured the novel like a musical canon, so by the end you have these multiple layers. If you listen to a fugue by Bach you want to hold on to the theme but it’s impossible. It gets incredibly complicated.”

Cath’s thesis concerns Sebald’s strange poem, Bleston: A Mancunian Cantical [sic], and the literary dialogue between the two writers across the decades. Both appear to have projected onto the landscape of post-war Manchester, with its darkness and its sprawling streets, their respective horrors of the second world war: the occupation of Paris, the Holocaust.

Before Butor in the 1830s, as the academic well knew, French historian Alexis de Tocqueville had famously described newly industrialised Manchester as a “noisome labyrinth”.

After him, in Sebald’s novel The Emigrants, the ash-strewn rain so often referred to in Passing Time is repurposed in depicting the city as a notional concentration camp.

As for Butor himself, says Cath: “He wrote very little in the way of autobiography but there are fragmentary pieces. He’s said you can see Paris behind the mask of Bleston, which on the face of it is a bit of an odd thing to say, except that during that period in the early 1940s [when the author was growing up] occupied Paris was dark, there was smoke, there were fires, there was violence, there were betrayals…people disappeared in the night and nobody spoke of it afterwards.”

Back in Manchester I swap emails with Jonny Walsh at Pariah Press. As a publisher of leftfield and outsider literature this seems right up his street. To my excitement Jonny agrees. So we get together and read up on Butor and his world, and the strange books he wrote in bespoke structures reflecting their themes: a labyrinth in Passing Time; a return train journey in the cris-de-couer novel Second Thoughts; a fragmentary scattershot in his landscape portrait of the U.S., Mobile. Thus, we encounter the “bridge” he attempted to construct in the novel form between philosophy and art: Butor thought literature could rewire you, transform you. His novels are vessels for doing this.

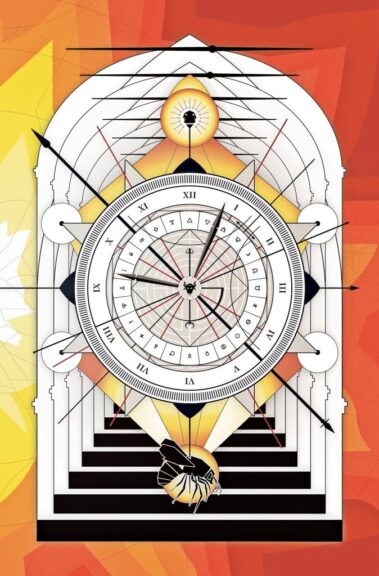

Pariah get on the case. Jonny makes enquiries to the original publisher, Les Editions de Minuit, and the estate of the translator Jean Stewart, eventually acquiring the rights to the English version. Over lockdown Cath, Jonny and I comb the text for errors and typos. Colleague Steve Cherry designs a new cover, a dizzying clash of space and time in flaming hues recalling the fires that seemingly break out across Revel’s Bleston. Then the manuscript is off to the printers, the book is published and made available for sale for the first time in decades. A lost classic of Mancunian literature…you can buy and read it yourself now from the Pariah Press website.

So what is it really all about? “Memory,” suggests Cath. “The attempt to hold on to who you are as it is assailed by life. And I think there’s definitely the influence of Proust. You look at these long, flowing sentences and the way they carry on…”

Personally, I think it’s about a man who becomes slowly consumed by the logic of fiction, only to find when applied to real life it sends him spiralling into madness.

Whatever the reading, the next step in the Butor revival is set for early next year, with Vanguard Editions due to publish a selection of the writer’s essays, setting out his unique perspectives on the novel. The Parisian, who died in 2016, is renowned in his home country for the novel Second Thoughts (also known as Changing Tracks) which is taught in schools, and is commonly – perhaps uncomfortably – pigeonholed with the avant-garde school of French writers labelled as exponents of the nouveau roman.

“He was a real one off,” says Vanguard’s Richard Skinner, who only learned of the writer’s existence from one of his students at the Faber Academy. “A great mind and a great intellect but no one really knows him in the anglophone world. He had a very singular, fascinating vision…this polymath who in some ways reminds me of Erik Satie.”

His brief stay in Manchester in the early 1950s, the strange Proustian novel which resulted, his impact on W.G. Sebald, the way he ties depictions of the city across the ages…these things are the stuff of high art, yet to be assimilated into the Mancunian cultural narrative.

“I love eccentrics,” says Skinner. “And I’m very drawn to people who don’t live within their normal expectations within society. I think Michel Butor was a bit like that.”

You can buy Passing Time at the Pariah Press website – click here

Catch Danny Moran on Twitter: @dannyxmoran

The Meteor is a media co-operative on a mission to democratise the media in Manchester. To find out more – click here.

Sign up to The Meteor mailing list – click here.

Featured image: composite of Pariah Press cover art for Passing Time, by Steve Cherry, and image of Michel Butor.

Egmont Labadie says

Dear Danny Moran,

thanks for this very interesting work around Butor. He was a most singular author, in a very experimental fashion, and his memory has been a bit lost in recent times, even in France.

For lovers of philosophy, you can certainly draw interesting lines between his work and Gilles Deleuze’s conceptions. Mobile is a very Deleuzian book…Which you can also read thinking about Calder’s mobiles…It kind of works the same way.

A great interest of Passing Time is the way Revel’s changing opinions about the city reflect the very evolutions of his mind, until the end of the book when this city he didn’t like at first glance has become part of his life. I guess every one having to spend some extended time in a new environment will have to live through this kind of psychological adventure. I did !

Second thoughts, although with a very minimal setting, is a captivating novel, where the reader becomes the main character from the very beginning…It is a quite existential experience, very 1950s like !!!

I met Michel Butor once, he was a very kind, highly intelligent but humble person, like a craftman of litterature, who didn’t get the broad recognition he would have diserved…In a way it explains why all of his works, even the most anecdoctic ones, are always of great quality.

In the end, Michel Butor can end up being like an old and dear friend, to which you will always have pleasure to come back to. That’s what happened to me anyway !

All the best,

Egmont

Paris, France