Manchester is undergoing incredibly rapid change. Construction cranes dot the skyline of the city in increasing numbers and they appear to be steadily migrating out of the centre. Change is also occurring due to austerity driven cuts which are limiting the availability of local public services, and changes in shopping habits are having a devastating effect on high streets across Manchester and the UK. Not too far from the city centre is Miles Platting, where residents are experiencing redevelopment, and the closure of services and shops after many years of relatively little change.

But when it comes to the huge amount of urban development occurring across Manchester: whose knowledge matters? That is the question an innovative research project from the Urban Institute, University of Sheffield, has addressed by asking the residents of Miles Platting how these changes, and the planning process that proceeds them, affect them. The people who have to live with the consequences of these changes.

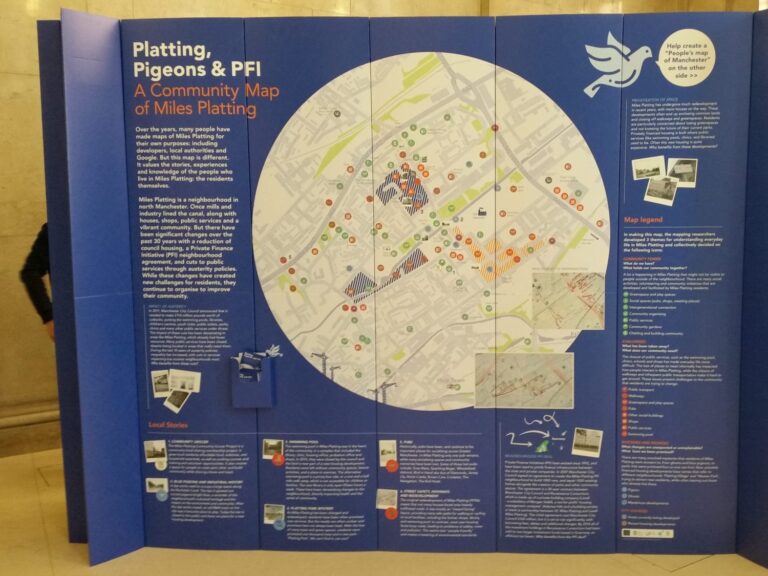

An exhibition displaying the results of the project is available to view and interact with until the end of August, as part of the Peterloo 2019 commemorations of the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre. The map of Miles Platting that researchers and residents produced with the aid of the diverse local knowledge of the wider community of Miles Platting is being exhibited on the first floor of Manchester Central Library, along with stories and images provided by the residents that give a rich and varied insight into the neighbourhood. It is an ongoing work and people attending the exhibit can suggest facts, stories, images or memories to add to a larger map of Manchester, using the icon stickers and notebook provided.

Lament for the local library

Speaking to the Miles Platting residents at the opening of the exhibition in the beautiful bastion of knowledge, education, equality and culture that is the Manchester Central Library, a recurring feeling encountered was a sense of loss due to the closure of their local library.

Yves Kinsi has lived in Miles Platting for 20 years and believes the area has lost too many important services, which has had a negative impact on his family and particularly his children:

“We used to have a beautiful massive library… [Now] kids more or less have to come to the city centre when they have an assessment to submit. They will spend days and days in here to make sure they come on top of their assessments. But it used to be next door, you go there, everything is safe and we know where you are. Being in town, with a lot of knife crime in the country – it is a bit terrifying”

The physical health of his family is also a concern for Kinsi, alongside his concern for their ability to enrich their minds:

“We have lost a lot of facilities. We have lost the swimming pool, gyms, things like that. Playgrounds for kids have been demolished and new houses have been put on… I used to go swimming with the family, it used to be about a five minute walk.”

Speaking about the development process in the area Kinsi explained “we just kind of feel powerless,” and due to it being a local government accepted project he felt there was “nothing you can do” to change the outcome.

Another resident who expressed concern for the loss of the library was Eric Keeble, a former structural engineer and academic, who retired and bought a house in the area in 1998:

“We have lost the swimming pool and the really nice 1970s library. It was a really generous building and pleasant space, and [we lost] the immediate local shops, which did struggle to survive as people’s shopping habits changed.”

Libraries are under threat across the country due to austerity budgets forced onto local councils. Between 2010 and 2016, 478 libraries closed across the UK. In 2017-18 there were 130 libraries closed across Britain. And increasingly the libraries that are left are being downsized and only kept open by the goodwill of volunteers. In 2010 an estimated 10 public libraries were in the hands of volunteers; by 2017 the figure had risen to 500.

A smaller community library has been provided in Miles Platting, which still has a council paid staff librarian, but is dependent on volunteers to function for the limited opening times it is available. Kinsi believes it is not an adequate replacement for the old library, as his children now prefer to travel to the central library to study.

Keeble also missed the loss of green space in the area, due to housing developments that have been built on the land that the library and swimming pool used to stand on and the green areas that used to surround them:

“That was one of the nice things about it. It wasn’t quite like living in parkland, but there was a lot of green. It was refreshing not to live in an endless sea of housing and it is becoming much more like an endless sea of housing now, which is a shame.”

Platting, Pigeons and PFI

Professor Beth Perry and Dr Victoria Habermehl are two of the researchers from the Urban Institute at the University of Sheffield who have been working on the project through its three phases over three years. The first phase involved talking to the town planners in each of the ten boroughs of Greater Manchester about the controversial and since rewritten masterplan for the region – the Greater Manchester Spatial Framework (GMSF).

The second phase of the project involved a collaboration with Mark Burton of Steady State Manchester, and other organisations who were interested in identifying problems and possible solutions to the current planning process. The third part involved partnering with Miles Platting community members. Habermehl said at the opening of the exhibition:

“This project is trying to work with residents themselves to try and understand what knowledge was being overlooked, so not looking at planners’ ideas, in that sense… this process is trying to value community knowledge about Manchester, and say that matters a lot.

“This gives us an opportunity to ask the decision makers what are the different ways that these sorts of knowledges could be better listened to in the decision making processes.”

To present the information gathered in an accessible and visually stimulating way Habermehl and graphic designer Dan Farley, with help from Counter Cartography expert Liz Mason-Deese, created a map with icons to illustrate where each piece of knowledge referred to in Miles Platting. Mason-Deese describes counter cartography as a “militant research” mapping technique that aims to “foster cooperation among researchers and participants to practically intervene in real problems without attempting to marshal state or administrative power”. Farley says the next step is to produce a larger “people’s map of Manchester” which they aim to provide as an online resource.

The community map they produced was put under the title of “Platting, Pigeons and PFI”. The pigeon in the title refers to the fact that a dye works formerly situated on the Rochdale Canal used to dump waste blue dye effluent into the canal, that used to turn nearby pigeons a bright blue. The PFI refers to a proposed Private Finance Initiative funded housing development that underwent an extensive public consultation process, but this first PFI plan was abandoned due to the financial crash of 2008.

The mystery park

Keeble remembers well the ultimately doomed first PFI public consultation, which he took an active part in and voted for one of the two schemes initially presented:

“They went into quite a thorough process of having an exhibition at the library and open sessions. It was reasonably well participated in… there were enough people with a view or [who] had an opinion… All that was really relegated to history as far as I am aware because that particular development didn’t proceed in that form.”

When it comes to planning decisions and public consultation it is the PFI deal that the residents of Miles Platting bring up rather than the GMSF. Habermehl says:

“Prior to the crash, people were consulted about what they wanted to happen in Miles Platting in the redevelopment when the neighbourhood PFI was agreed. Because of the 2008 crisis the developer backed out of that deal of which they had been consulted on. The new development isn’t at all based on the previous consultation that had happened and which they had inputted in. So I think there is a feeling of frustration that they had already inputted into that previous process.”

The abandoned first PFI scheme, Keeble says, had a lower density housing element, and took up less green space than the second PFI scheme, which contained significant changes that the residents were not fully consulted on.

It is this discrepancy between the thorough public consultation for the first PFI plan, which was then abandoned and replaced with a second PFI plan, that has led to some mysteries present on the map. Due to the loss of trees and green space in the second plan, the residents were promised 1000 trees in a new “Platting Park’. No park has been created leaving residents feeling that a promise has not been kept.

Another resident who shares Keeble’s concerns about the loss of green space is Phillip Cartledge, a resident of Nelson Court, a block of flats in Miles Platting, for 16 years. Cartledge is also a songwriter, and a song of his is included on one of the boards adjacent to the map.

“They are going to build on the grass over the road, and to me it’s going to be too much. It’s nice to see a bit of grass and open space. [They are building on] any bit of land. It looks too cluttered and they have built the houses, but they have not given us any shops or facilities.”

Cartledge added “I just feel like you have no say in what goes on”, in regards to development in the area.

Another result of the redevelopment is that Miles Platting has become a more difficult place to navigate on foot due to passages and walkways being blocked off by the redevelopment. Habermehl says, despite enquiries, it is presently unclear whether some of these routes will be reopened once the development finishes.

Solidarity at the Community Grocer

In response to the local shops closing down, the residents have banded together to form a Community Grocer, which has become an important social hub for the area, even though it is only open one day a week. It is a community food sharing membership programme that gives local members access to reasonably priced food and household essentials. The resident participants of the Whose Knowledge Matters project were mainly recruited at the Community Grocer.

Kinsi also says that there are other positives to the developments in the area:

“The good thing is when you have new houses around the area looks structurally new, good looking. And quite a few civilised people coming around as well, compared to what it used to be 20 years ago. Well, the things I witnessed years back, I do not want my children to witness today.”

He also thinks that the WKM project has been good for pinpointing facilities that are missing in the area, which might prompt the council to do something about it.

There is a negative stereotype associated with Miles Platting and the people who live there, Cartledge suggested and thought the WKM project “might change people’s opinion of the place.”

The WKM project members invited along their local Councillor June Hitchen to the opening of the exhibition. Hitchen arrived and discussed the issues brought up in the map with residents. The limited opening times of the library was one subject raised, and Hitchen asked the residents to decide what extra hours they would like the library to open and said that she would then try to make progress on the issue.

Whose knowledge matters?

As Habermehl had taken part in this project from the beginning and had questioned lots of planners, community organisations and residents, I asked her whose knowledge does matter when it comes to building development plans and changes to local services:

“I think this process shows local residents have a great deal of knowledge about where they live and that should be taken more seriously and earlier in the planning process. I think that is the idea of the map, it shows the knowledge that residents had that wouldn’t necessarily be regarded in a formal process because it’s a different sort of knowledge.”

Habermehl went into further detail on the problems she sees in public consultation stage of the planning process, that the WKM project had highlighted:

“I think it [public consultation] comes too late in the process. The point of this was that we didn’t want to base it on the way the planning system already works, that would just be asking people to give an opinion after it has already been set out. The point of this was taking it from the perspective of communities themselves first. I think that is a problem with the consultation, you just consult at the end when you have an idea and you are trying to get it past people.”

It is 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre, where thousands gathered from across the region to demand suffrage, the right to vote. At that time only the male members of the propertied class and the landed gentry had the right to vote in elections. For their troubles they were massacred, on the orders of the local landed gentry, by the mounted Manchester and Salford Yeomanry. Many were drunk, and all were brandishing sabres which they used to kill 18 people and wound 400-700 more.

The marchers at Peterloo were calling for the right for their collective knowledge to matter in the elections that would send members of parliament to Westminster to represent them. Those marchers would surely approve of the current Whose Knowledge Matters project and its attempt to empower those who often feel powerless when confronted with the often mysterious plans that will affect their lives presented to them by those in power.

Conrad Bower

For more information on the Whose Knowledge Matters project – click here

Tell the WKM project team what you thin using #KnowledgeMattersGM

For more information on Peterloo 2019 events – click here

Read: A democratic media for Manchester

Check out The Meteor’s homepage for our latest stories

Featured image and in article images: Conrad Bower

Amendment to article 3 July 2019: “Centre for Urban Studies in Sheffield” was changed to “Urban Institute, University of Sheffield”. Some changes were also made to make it clear that the development plan that went ahead in Miles Platting was also a PFI devlopment deal, but was to a different specification to the first PFI deal which collapsed due to the financial crash in 2008.

Leave a Reply