The war on drugs is a conflict without end. Significant and growing collateral damage is caused to society and to the individuals who take drugs, with a growing number paying the ultimate price as covered in part one of this story which documented the damage caused under our current prohibitionist policies towards drugs. There are alternatives to how we deal with this perennial problem that have the potential to revolutionise how we manage drug use in this country, that are already being pioneered in others.

Drug decriminalisation

In 2001 Portugal took a long hard look at the evidence around drug use by its citizens and instead of continuing to pursue their drug policing strategy, they took the radical yet rational decision to do things differently. They decided to view drug use as primarily a health issue and decriminalised low-level possession and consumption of all illicit drugs. Rather than being arrested, a person found in possession of small personal amounts of any drug is ordered to appear before a local “dissuasion commission” comprising of health, legal and social service professionals, who decide if the person is addicted to drugs, and to what extent. The commission can then, take no further action if the drug use is non-problematic, refer them to voluntary treatment programmes, or impose a fine, or community service. There is no punishment by imprisonment and no criminal record produced.

As in the UK now, there were doubts in Portugal back in 2001 about the negative affects the liberalisation of drugs laws might have on society, “There were fears Portugal might become a drug paradise, but that simply didn’t happen,” said former Portuguese police chief Fernando Negrao in 2007.

Drug overdose deaths (DOD) dropped rapidly after decriminalisation was introduced in Portugal, in 2001 they stood at 7.35 per million of population, by 2005 that figure had dropped to 0.86, an 88% drop. Since then there has been a slightly increasing trend in drug overdose deaths with 2018 recording 5.36 deaths per million, which is still 27% lower than 2001, according to European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Addiction (EMCDDA) data presented in the graph below.

The comparison to drug deaths in the UK within that time frame, is shocking. In 2004 the UK’s DODs stood at 35 per million, which is 18 times greater than the figure of 1.91 per million in Portugal the same year. In 2017 there were 49 per million DODs in the UK and 4.96 in Portugal, a 10-fold difference. The graphic above shows that the UK has been experiencing a rising trend in DODs since the lowest figures in 2010, with a 52% increase in DODs from then till 2017.

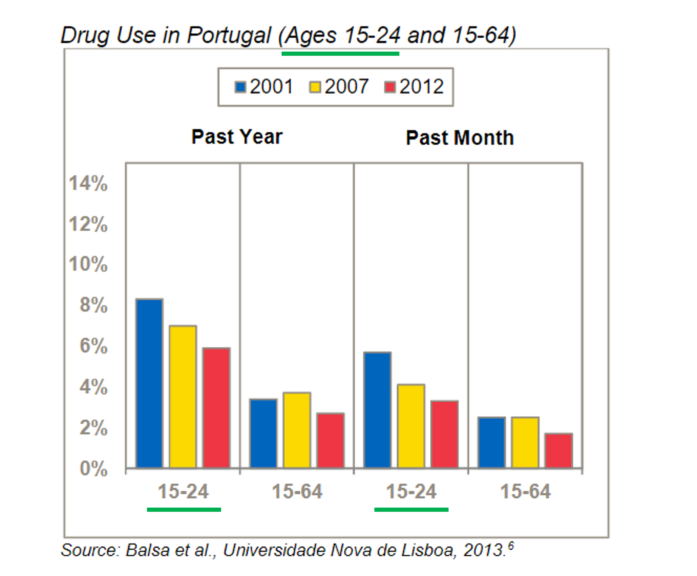

One of the many fears associated with liberalising laws around drug use is that it will encourage youths to take drugs. Portugal, between 2001 and 2012, saw a sustained decrease in 15-24 year-olds saying they had taken drugs over the past month, or year. Smaller drops in self-reported drug use were also observed in 15-64 year-olds over the same period.

Alongside the drop in drug related deaths and youths using drugs, there have been many more benefits as noted in a Transform report in 2021. Those imprisoned for drugs related offences has dropped from 40% of the prison population to 15%. Prior to decriminalisation Portugal accounted for 50% of the EU’s annual HIV diagnoses linked to intravenous injection of drugs, that figure has dropped to 1.7%. And the country’s rates of drug use have consistently remained below the average across the EU.

Dr Lisa Williams is a senior lecturer in Criminology at the University of Manchester, whose research focuses on recreational drug use and how that use may vary and adapt as a person gets older. Williams believes the decriminalisation strategy in “Portugal has been a success. It has seen people diverted away from the criminal justice system, and so the incarceration for drug offences is reduced.

“Drug use and problematic drug use has decreased as well, and I think Portugal’s got one of the lowest rates now in terms of drug use in Europe… But from what I understand about Portugal’s success, it’s not just the decriminalisation policy, it was matched with health and social policies… So we could say decriminalisation is the way forward, but I think for it to be successful we have to match it with other funding into health and social policies, around employment and housing particularly.”

In a similar vein to all the experts on drug policy that contributed to this article, Williams believes that decriminalisation doesn’t go the whole mile when it comes to reforming drug policy to gain maximum benefits, saying:

“I generally feel that decriminalisation is a good first step potentially, but it is a kind of halfway house as well. We still leave the illegal market there for people to come source their drugs from, and the illegal market is about profit and causes harm to people through the substances that are cut with other more harmful substances, and no regulation over the potency of substances. The reason that we have a high number of drug related deaths in the UK is that we’ve seen the change in potency of certain substances.”

Substances such as heroin which when mixed with Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 1,000 times more potent than heroin, has led to a spate of overdose deaths across the US and UK. The average UK street strength of an ecstasy pill in 2017 was 156 mg, but doses can vary wildly in quality and quantity. Robert Ralphs, Professor of Criminology and Social Policy at MMU, carried out drug testing in Manchester clubs and says that on the same night they found ecstasy laced with ethylene and alpha PVC, they also tested “the world’s strongest ecstasy pill at 477 milligrams” of MDMA.

Drug legalisation

Alongside the benefits of controlling the quality and quantity of psychoactive drugs, with its health benefits for users, a legalisation model also offers the opportunity to bring a large part of the £9.4 billion a year drugs black market in England and Wales within the legal economy. A legalisation model depriving organised crime of funds could also drastically reduce the estimated £19 billion a year cost of the health harms, costs of crime and wider impacts on society, due to drug use.

Esther Kincova, from Transform, believes a “full national decriminalisation model” is needed leading to “what ultimately would be legally regulated markets” for the full benefits of drug policy reform to emerge. Bringing this black-market money into the economy could also provide further benefits Kincova says:

“If you’re taxing it, that money should be put back into people who’ve been most adversely affected by drug use and drug prohibition as well… I’m talking about the kind of 10 to 15 percent [with problematic drug use], rather than people who are just going out for the weekend and having some fun.”

Legalisation is no panacea to the problems that drugs cause to individuals and society, Kincova says, “there are so many systemic issues and intersectional issues that we don’t think will just be gone with legal regulation” but it could lead to a “step change in society about stigma around drugs if we see them legally regulated” similar to, but more strictly than, alcohol and tobacco.

Marijuana legalisation

It is with some irony that the US, the main protagonist in the war on drugs, is now leading the way in legalising one of Richard Nixon’s major bugbears – marijuana. It was under Nixon’s administration in 1972 that marijuana was placed in the “Schedule 1” designation, meaning it was regarded as one of the most dangerous of illicit narcotics, equal to heroin, by the US federal government.

The US Drugs Enforcement Agency considered marijuana to be of no medical use, despite evidence suggesting cannabis resin made from marijuana has been used as a medicine for thousands of years. The DEA’s extreme prohibitionist stance on marijuana, which severely limited medical research into it, went against the weight of evidence and experience with the drug, summed up by US oncologist Donald Abrams’ comment that “not a day goes by when I’m not recommending cannabis to patients for nausea, loss of appetite, pains, insomnia and depression—it works.”

The Federal system of government gives individual states power to pass their own laws on the use of drugs within that state, and after looking at the evidence around the use of marijuana many have decided the best way forward is to legally regulate it. Colorado and Washington were the first to do so ten years ago and now eighteen states have legally regulated cannabis for medicinal and recreational use.

Change appears to be spreading from the ground up, and influencing the Federal government’s previously inflexible stance, Kincova says, “There are now two bills in the Senate. One Republican, one Democratic, and they’re both about federally, legally regulating cannabis. That’s a huge step change.”

Other countries are following suit, Uruguay, Canada and Malta have also legalised cannabis and Germany’s coalition government, has commenced talks with stakeholders on legalising recreational cannabis, which was a manifesto promise prior to the election. Kincova believes that if Germany legalises then a domino affect will occur through the rest of the European Union.

If legalisation was to occur in the UK then cannabis is likely to be the first contender. And with Tory Party MP’s such as James Cleverley and Victoria Atkins having family links to medicinal cannabis companies, who will be well placed to profit from recreational use being legalised, there is likely to be significant corporate lobbying of government occurring to go down this road.

Although Transform and Kincova want to see cannabis legalised she is wary of the free marketeer’s bonanza that could occur if it is done badly:

“We can’t think of anything worse than seeing billboards for cannabis, and cannabis adverts, and cannabis drinks because we’re not advocating for access to cannabis, for access sake. We’re doing it as a public health issue. We do not condone drug use and we do not want to see the increase of cannabis use, we just want it to be safer and to take that kind of lucrative market away from criminal groups.”

When it comes to legalising cannabis Kincova says it “needs to be in the interest of the public health” and that there needs to be “social justice aspect” to it and “mitigating corporate capture is extremely important. We do not want to end up in a situation where we have the lobbying power of alcohol and tobacco that has been allowed.”

These concerns around how cannabis is regulated were echoed by Ralphs, who also raised the concern that the decriminalisation and legalisation debate in the UK often boils down to cannabis, and there is a general fear of liberalising harder drugs such as heroin. Ralph says:

“The biggest benefits of decriminalising drugs seen from Portugal, have links to the heroin users and injecting drug users. There’s been a reduction in blood borne viruses, more people in treatment, less people injecting and drug related death.

“So quite often people say, ‘well I wouldn’t decriminalise heroin’. Well, that’s where the main benefits are also in terms of criminal justice system gains. Quite often people take the view, ‘we would decriminalise cannabis because there’s more people use cannabis, so that would divert more people away from the criminal justice system’. But the biggest benefits are around decriminalising or regulating heroin markets.”

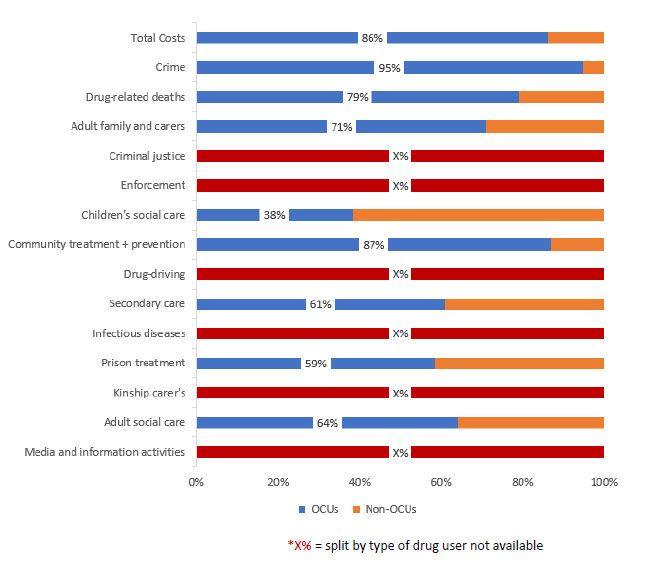

The costs to society of illicit opiates and/or crack cocaine users (OCUs), and users of other drugs (Non-OCUs)

Steppingstones to a healthier drugs policy

The common consensus amongst the experts spoken to was that the chance of a radical overhaul of drug policy, with a broad decriminalisation or legalisation agenda covering a range of drugs, was pretty slim in the near future. But there are steppingstones in place in the UK, and ones that could easily be placed, taking a public health first approach to drug use that are showing positive results.

As Ralphs points out, users of illicit opiates (such as heroin) and crack cocaine (OCUs) are responsible for a large number of the drug overdose deaths in the UK, primarily because a large proportion of them will use intravenous injection to deliver their high. These drug users are also account for 95% of the cost of drug related crime to public funds, so initiatives aimed at this group can provide large public health and wealth returns, alongside transforming the lives of the people concerned.

Heroin assisted treatment (HAT) is one such initiative which involves providing people addicted to heroin with medical grade heroin (AKA diamorphine), once or twice a day when they attend a medically supervised clinic. Heroin users using the sterile facilities and injecting equipment have fewer wounds and infections, and no one overdoses because they are given carefully measured doses of prescribed diamorphine. The HAT schemes provide an avenue into drug treatment for users and eliminate or significantly reduce acquisitive crime and sex work undertaken to fund use. They also reduce street injecting and the associated litter. Everyone’s a winner apart from the heroin dealers.

This is a steppingstone already in place with small HAT trials being carried out in the northeast and Middlesbrough, Ralphs says that there is ”about 20 years of evidence showing this works in Switzerland. And the evidence, even though its only small, it is positive in some of those trials in the UK. And I think it is a positive that we have actually commissioned these trials.”

In a similar vein to HAT schemes there are Overdose Prevention Centres (OPC), which provide a sterile safe space to inject, but do not provide the drugs themselves. Kincova says:

“There’s almost 200 of them around the world, yet the Home Office does not want to open one because it says it’s in contravention to the Misuse of Drugs Act. Yet there have been no overdoses recorded in any of these that have been running, in some of the oldest ones I think that’s almost three decades. So the statistics on their success is absolutely incredible But they also offer amazing wrap around services for the people who come into contact with them.”

Ralphs also believes OPCs are the way forward, saying, “for me there’s no negatives, and dozens and dozens of benefits. The evidence base for them is so huge and so well established and so consistent.

“It just beggars belief. Over a third of drug related deaths [across Europe] occur in in the UK and now that’s kind of gone up again.

“The government seems so against them, despite the evidence and the huge increase in drug related deaths. It’s something I would love to see happen locally, and across the UK.”

Drug Diversion Schemes (DDS) are another steppingstone in place in the UK, that offer a type of decriminalisation route away from the criminal justice system (CJS), and towards support, for drug users. This is a change that is being championed locally, a ground up approach, put in place by police forces around the UK responding to the evidence on drug use and enforcement.

These schemes can operate pre-arrest leading to a less serious out of court outcome, or post arrest diverting the individual away from a court hearing where they are likely to be convicted. The individual concerned may be diverted to a Community Resolution, a caution or a deferred court summons, each having obligations the individual will have to abide by if no further action is to be taken against them, and the incident not recorded. A key part of these schemes is that the obligation taken on by the drug user to avoid prosecution and processing through the CJS, is often to engage with support and services related to their drug use.

Across England DDS are already operating in Durham, Bedfordshire, Cleveland, Devon and Cornwall, Hampshire, Hertfordshire, Kent, Leicestershire, Thames Valley, and the West Midlands.

No DDS is currently running in Manchester but Greater Manchester Police are currently reassessing their drugs strategy in light of the government’s 10 year plan for drugs which was released just before Christmas, and Ralphs who has worked with GMP and GMCA during his research believes that the “decriminalisation of small amounts of personal usage of drugs… will certainly be on the table for discussion.”

All the experts spoken to in this article have devoted a large part of their working lives pouring over the evidence and investigating drug use in the UK. And they, like the majority of people who weigh up this evidence, have come to the rational conclusion that drug policy has to radically change, to reduce the harm caused to the individuals taking drugs, and to our wider society. Williams I believe sums up this consensus, saying:

“Prohibition doesn’t work, we know that. That’s what I teach to my students. Prohibition has clearly failed… There isn’t a perfect solution, so we need to move to look for something that can work, and either decriminalisation or legalisation could be better.”

The only winners in the current war on drugs are the organised crime gangs profiting from this extremely lucrative and violent trade. Progressive evidence-led change in UK drug policy, could divert this considerable wealth into bolstering society rather than undermining it and improve the health and life chances of millions of UK citizens.

For part one of this story – click here

For a wealth of information on drug policy reform – click here

Sign up to The Meteor mailing list – click here

The Meteor is a media co-operative on a mission to democratise the media in Manchester. To find out more – click here

This story is part of the Creating Radical Change series

Featured image: Public Domain Pictures, Flickr, Wikipedia Commons

Leave a Reply