It felt like the aftermath of a revolution. Wandering through the University of Manchester’s (UoM) Owens Park campus in the early hours of 6 November 2020, with bits of mangled fence scattered across the ground, the failings of our hyper-marketised higher education system were there for all to see.

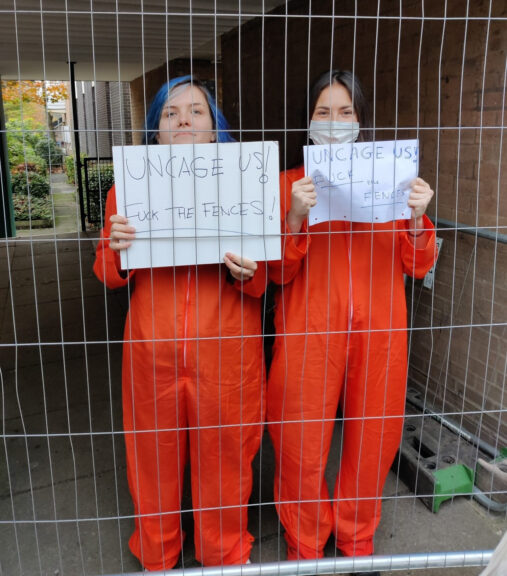

Freshers had been promised in-person teaching by their universities and the government, in spite of warnings from the University and College Union (UCU) and SAGE, that this could be risky. After just a few weeks, with a second national lockdown in place, it was clear that this wasn’t going to be the case. New students, living in a new city and often living away from home for the first time, were trapped in dull accommodation blocks, with massive amounts of COVID cases. To add insult to injury, with no prior warning, fences were erected around the Fallowfield campus, preventing students from even going outside. Thankfully, it only took a few hours for all the fencing to be torn down by students. In a similar vein, security guards were positioned outside accommodation at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU).

This debacle was just one recent example of how little care the UK’s Universities – in particular UoM – have towards their students. Thanks to the ongoing marketisation of higher education, with £9,250 tuition fees, universities have shifted from institutions of learning to profit driven machines. Students have now become consumers, paying for a “product” (a degree). This means, as Cambridge student Daniella Adeluwoye argued last year, their “rental incomes matter more than education”. This process is enabled by national government, who are content for universities to act as a “for-profit business.”

When you view students as consumers, it becomes much easier to understand why universities were so keen to get freshers on campus despite the risks involved. Universities rely on their income – through their fees, rent payments and money spent on campus – to stay afloat at whatever cost. They could have followed the advise of the UCU and SAGE who argued in-person teaching was not safe and advised that students stay at home for the time being. Instead, they doubled down on their efforts to collect rent. It took 15 days of students occupying the disused Owens Park Tower block for senior management to step back from their threats of expulsions and grant a 30% rent reduction.

But don’t be fooled into thinking that all this revenue goes back into improving the quality of teaching. As lecturers across the country (including some at UoM), have been forced into three waves of strike action in the last two years – citing diminishing pensions, excessive workloads and insecure contracts – vice-Chancellors have inflated their own salaries. Despite the announcement of 528 redundancies at UoM last year, Nancy Rothwell still collects a £260,000 salary. This greedy practice was described by a former proponent of tuition fees in 2017 as a “cartel” which should be brought to an end. As of 2016, 75% of UoM’s academic staff were on insecure, temporary contracts – a number likely to have risen since.

Rothwell often found herself centre stage of controversy over the past year. In one notable case, she falsely claimed to have apologised to Zac Adan, who was the victim of racist treatment by UoM security staff.

UoM’s questionable investment choices doesn’t stop there. “They are renting space to fast food restaurants while claiming they don’t have enough money to properly fund pensions or equal pay for women and black and minority ethnic staff”, said one Manchester lecturer doing the 2019 strikes, referring to the new bars and restaurants on University Green. It was only last year that senior management pledged to divest from fossil fuel companies as well as Caterpillar, a construction company used to demolish homes and communities in Palestine. In all these cases, UoM put money over morals. It was thanks to the works of groups such as People and Planet and Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions that forced senior management to think again.

The following academic year will likely be a bit less frantic thanks to the positive effects of the vaccine and much more knowledge surrounding the virus and getting tested for it. However, many questions about our Higher Education system remain. The current model of universities operating for profit has largely been a failure for staff and students alike.

There doesn’t seem to be much political impetus to discuss this issue. However the movement that emerged around campuses last year, featuring a range of campaigning groups, is a positive step and one that can’t be built on. It must be ensured that demands made do not simply revolve around a reduction in fees, as such arguments further entrench the idea that students are consumers asking for a refund, rather than a group of people insisting on real change. Free university education, funded by progressive taxation, is not an unreasonable, utopian demand – it is the reality in many countries around the world. The abolition of tuition fees and replacing loans with grants, therefore, must be top of the agenda. Manchester’s students have played a huge role in revolting against the current order. Now they can be pioneers in building a new one.

The Meteor is a media co-operative, if you would like to find out more about joining and supporting our work – click here.

Sign up to The Meteor mailing list – click here.

Feature image: UoM Rent Strike 2020

S says

The vast majority of British universities are non-profit. I think the word you’re looking for is ‘revenue’.

Conrad Bower says

Hi S,

The University of Manchester does have status as a charity, however the author in this piece argues that the government is allowing Universities to act as a for profit business. Also revenue refers to the total amount of money brought into the University due to sale of its good and services and not the surplus, or profit, left behind when the costs and expenses are taken away. So I do not think that the word ‘revenue’ is a suitable alternative for ‘profit’ in this article.