The digital divide in education, was already a cause of educational inequality before the pandemic struck.

“But then Covid came along and now we are really aware there is a divided wall,” says Professor Cathy Lewin, from Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) School of Teacher Education and Professional Development.

The Covid crisis has increased the sharp contrast between the two sides of the divide. One side populated by school children from more affluent backgrounds who have good access to digital hardware and online services. The other consisting of their poorer peers, who may have more complex and crowded family lives and little or no access to digital devices or the internet at home.

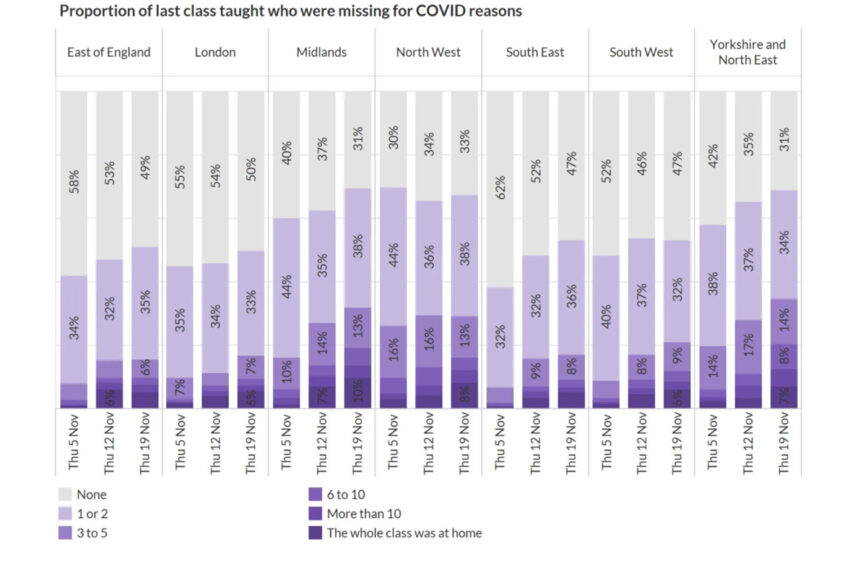

With the Covid-19 lockdowns and many Covid related student and teacher absences along with widening gaps in learning due to online classes hindered by lack of connectivity, the inequality in education grows as the poorest students are left out. Children in Greater Manchester are being hit particularly hard due to the high levels of deprivation in the region, and a large number of children missing classes across the North West, due to Covid during the last lockdown.

The digital divide before Covid

The problem was already deeply entrenched before Covid-19 forced schools to close and remote learning became the default option for many. A UK government survey in 2018 found 700,000 students, 12% of 11-18 years old, had no internet access at home from a computer or tablet with an additional 60,000 having no internet access at all. Of the 11-18 year olds that did have internet access, 68% said they would find it difficult to complete their homework without it.

Before Covid, schools in advantaged circumstances were, Lewin said “more likely to put things in place that demanded the use of technology” which included live lessons, homework submission, and online assessment. This gave students more opportunities for instant feedback and engagement with teachers creating the virtual learning environments. In less advantaged areas, there was a greater reliance on paper based learning resources as the schools was more concerned about inclusion.

Lockdown

Lewin, told The Meteor that, “schools for a long time have been making provisions [for students without internet] by offering school clubs and access to libraries”. She feels that schools were conscious of making sure they were inclusive and were making provisions for students to finish small homework assignments at school.

“There is a huge difference between a 20-minute piece of homework that could be completed at school to suddenly switching to all online.” She pointed out that during lockdown it was encouraged to be all online and students could no longer use the school computers, access public libraries, or even pop over to a friend’s house to use their technology.

*Bradley and partner *Susan are teachers and have been able to compare experiences. Bradley, a former state schoolteacher, currently teaches 11-18 year olds in a private school, and Susan teaches in a deprived area at a primary school in Manchester.

Bradley noticed the huge difference as the parents of his pupils work in the professional sectors and have a type of role where they regularly check emails, do office work online, and have laptops at home while at Susan’s school there was a scheme of food donations provided by the school. Susan said:

“Parents are living hand to mouth and would come in [during lockdown] and pick up food and then go into another room to pick up schoolwork packs for their children because they had no internet access…if they had any internet access it was through phone data.”

Many of Susan’s students were on the free school meals scheme and any income was going to other bills and necessities and not to internet access or devices.

The reality of poverty in Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester Poverty Action reported that in 2018, Manchester had the 8th highest child poverty rate in the country with 45.5% living below the poverty line in 2017/18.

Huge gaps in learning then took place during lockdown according to a June 2020 report by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) called Pupil Engagement in Remote Learning.

The report found that disadvantaged pupil engagement was lower in the most deprived area schools and concluded that twice as many pupils in these schools have little or no IT access compared to those in the least deprived area schools.

Regional analysis by NFER indicated that there are less likely to be pre-recorded video lessons and online teacher-student conversations in the north of England compared to the south.

A University College London study found that by the end of the first lockdown, for primary schools, about half of teachers (47%) in the most disadvantaged schools said that the majority of their pupils were doing no work at home.

Bradley points out that in his private school, students absent now due to Track and Trace requests, can access schooling with live lessons with the ability to join in. They stay at home but follow their timetable throughout the day. He said, “my students are lucky…in state schools you cannot expect students to have computers or have the internet data on their phones to be able to do this.”

At Susan’s school, one day when the school had to be closed, lessons were uploaded online and only 10 out of 32 students in the class accessed it. They also found that parent embarrassment was a factor, they found it difficult to admit to not having internet access or the ability to help their children.

More than poverty alone

Research by Lewin discovered that lack of computers and connectivity in deprived areas that resulted in poor educational engagement were intersected with other factors such as no workspace in the home, noise and other family distractions, lack of parental support due to the needs of other family members, low levels of other home resources such as books, and sharing of just one device – usually a phone. The parent’s perspective on the importance of education also emerged as a factor, alongside parental language barriers, content knowledge and parent’s lacking confidence to help their children with school work.

An Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) report found that in April and May 2020, higher-income parents reported that their child’s school were offered more active help such as online classes and video conferencing.

Another key point revealed by the IFS report was that children from higher income families spent an extra 75 minutes per day engaged with home learning than children from poorer families. Equating to seven full school days’ more of learning time over 34 days of lockdown. The report found that one extra hour per week of instructional time can significantly raise educational achievement.

Private online tutoring was also identified by the IFS report as a big help to children from more affluent families, who spent on average more than five extra hours per week with a private tutor, compared to children from the poorest families.

Government failings

The UK government has done little to address the issue, Lewin says “there has been very little movement in the last 20 years” and with a crowded curriculum “teachers have so much to cover they haven’t time to spend thinking about how to integrate technology into the curriculum” and with Ofsted not looking at technology use during school inspections, “there are no drivers for schools to use technology”. There were initiatives promoting digital uptake but when the coalition government took over in 2010, they were more concerned with finances and “took their foot off the pedal” and “did not use any of the budget to invest in [educational] technology” Lewin says.

The Educational Policy Institute held a virtual round table in July, to discuss the digital divide, which Lewin took part in.

It was agreed that to support schools to adapt there was a need for centralised support and extra resources for teachers and students. Teacher’s must be offered training for remote learning and home learning for students should be supported with the distribution of 450,000 devices and internet passes. They also called for the regional differences in data infrastructure to be levelled by further investment and that wellbeing support be provided to students with stressful home situations.

Covid has brought forward the importance of technology in learning and also highlighted and widened the digital divide caused by children from less-affluent families having limited or sometimes no access to digital devices and the internet. The life-chances of these children will be severely restricted due to this lack of access, which is a waste of potential for them and for society.

There was a digital divide before Covid-19 and with the lack of computers and connectivity not being tackled, the learning gap will only get larger unless the situation is addressed soon.

By Dale Anne McAulay

* Bradley and Susan are not their real names as they wished to remain anonymous

The Meteor is a media co-operative, if you would like to find out more about joining and supporting our work – click here

To read more article in the Educational Inequality in Greater Manchester series – click here

Feature image: Wikipedia Commons

Leave a Reply