In a few weeks time, A-level and GCSE students across Manchester will be receiving their results for the academic year, not based on their performance in the usual summer term exams, but on predicted grades and teacher assessments.

Education secretary, Gavin Williamson, announced on 18 March that all exams would be cancelled due to Covid-19 and grades submitted by teachers will be processed by exam boards, such as AQA, to come up with a final grade, guided by the government exam regulator Ofqual.

Since this announcement, concerns have been raised by researchers, educators, parents and students about the potential for existing inequalities in the education system to be exacerbated, or at least perpetuated, by this predicted grading system.

It is feared that many students who were already struggling with the inequality of the education system are now finding themselves even further disadvantaged with the methodology being used to place students going on to A-levels, higher education colleges and university.

A report entitled Predicting Futures – Examining Student Concerns Amidst Coronavirus Exam Cancellations, part of the Equality Act Review Campaign, examined the concerns of students and parents regarding the use of predicted grades due to Covid-19 exam cancellation.

The majority of participants in the study came from BAME (Black, Asian, Minority Ethnic) backgrounds, with 80% of them worried about the predicted marks process.

Most students and parents were worried about two or more factors in the grading process. The top five factors participants were worried about were: that grades would be underpredicted, that students’ grades would not reflect their capability, that grades would not reflect the progress students had made since their mock exams, bias in the grading process, and that the grading system will disadvantage certain learning styles.

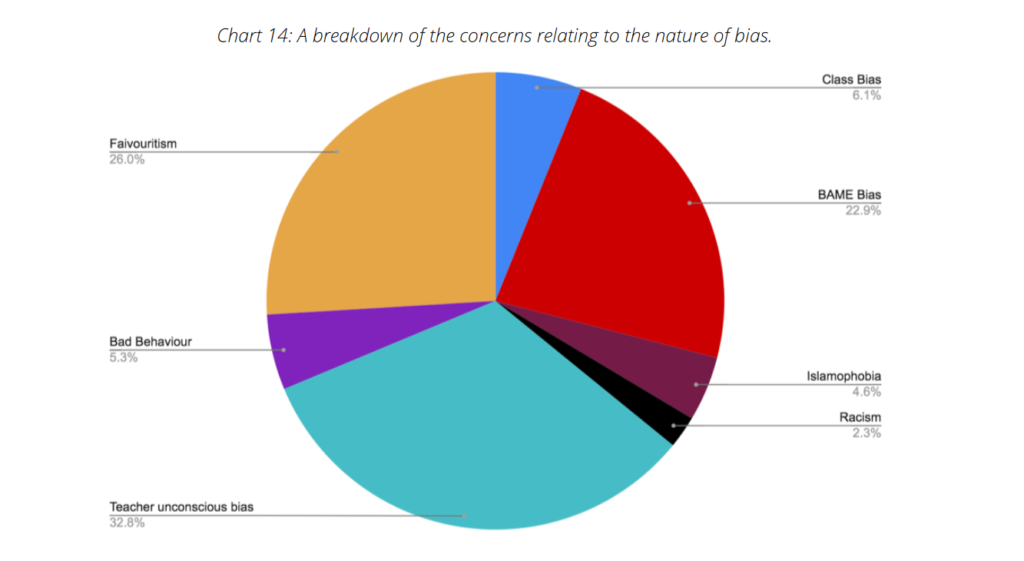

Concerns around bias included BAME identity as well as favouritism, bad behaviour, Islamophobia, and class.

The author of the report, Dr Suriyah Bi, told The Meteor, “As a working class, state educated, first generation to go to university, I would never have gone on to study at Oxford and Yale if my grades were predicted….I was told by my sixth form careers advisor I would receive five rejections from UCAS. Instead, I went on to secure a place at Magdalen College, Oxford…. All of this was possible primarily because I refused to believe that I was going to be rejected by all five of my university options….Stories like mine are common and under pandemic conditions are likely to worsen.”

Vik

Chechi,

science teacher and organiser

of the Northwest Black member forum for the National

Educational Union (NEU), agrees that exam predicted grades are a

problem for BAME students, as

this group have been

usually under predicted by their teachers in the past.

“In

schools [institutionalised

racism] is reflected by

Black students being more likely to be excluded, put in a lower set

in school or in conflict with zero tolerance policies on

things such as natural

African hairstyles”, according to Chechi.

He says that teachers unconsciously reflect bias and stereotypes, but added that teachers have been asking for training to help them with anti-racism, citizenship, and mental health issues in the classroom. However, austerity cuts, on top of a recruitment crisis, increased class sizes, and the pressure of exam results, have meant less resources and money for this kind of training.

Chechi also pointed out the findings in the Sutton Trust Report, Elitist Britain – 2019 which concludes that BAME people are more likely to be working class and that socio-economic diversity is still not being addressed in British education.

The Elitist Britain report argues that children from lower socio-economic backgrounds face significant obstacles throughout their life, falling behind before they even start school. From there the the gap widens as they continue in the educational system, which influences whether they attend university, which institutions they attend, and their entry into the workforce, as children from particular ethnic minority backgrounds are impacted by a form of ‘double disadvantage.’

“Within society you have a market for things like housing and employment and historically these have been on racialised lines. You are on the bottom of the pile if you are Black or Asian…[and] more likely to have a job where there are not many rights and it is lower paid. This is institutionalised racism,” Chechi explained.

Greater Manchester Poverty Action – Data analysis of the youth and play needs of children and young people in Manchester stated in their report that in 2018, 60.9% of school aged children were from a minority ethnic group and 40.9% of students were not first language English speakers. It also found that Manchester has the 8th highest child poverty rate in the country with 45.5% living below the poverty line in 2017/18, indicating a double disadvantage for many students in Manchester.

When asked if this was a problem of colour or poverty, Dr Bi replied that, “We don’t believe it is as simple as one or the other. Intersectionality theory is very relevant here. Identities intersect and overlap and so it is not possible to say it is colour or poverty. In fact, both intersect and exacerbate the impact on students who are from BAME and low socio-economic backgrounds due to low expectations of them and the lack of resources available to them.”

Almost half of UK Black African Caribbean households were found to be in poverty, compared to one in five white families, according to the latest report, Measuring Poverty 2020, by the Social Metrics Commission. People in Black and Minority Ethnic families are also between two and three times as likely to be in persistent poverty than people in White families, meaning that they have also been in poverty for at least two of the last three years.

Afzal Khan, MP for Manchester Gorton and Shadow Deputy leader of the House of Commons, runs a Young Leadership Programme and supported the Predicting Futures report. In it he writes, “As the MP for Manchester Gorton, which has one of the highest child poverty rates in the UK, I know full well the importance of opportunity for young people.”

Khan later told The Meteor, “The existing BAME attainment gap is more likely to have been exacerbated by this pandemic. Bias and other factors mean that predicted grades are not always a true reflection of a student’s potential. These concerns need to be looked at and addressed.”

The Predicting Futures report called on the government to ensure that the concerns raised by students and parents in the study would be taken into consideration, and on 21 July Ofqual stated that this year the numbers of students getting good grades will be 2% higher at A-level and 1% at GCSE compared to last year.

Ofqual have also stated that there is no evidence of any widening gaps in this summer’s results, in terms of ethnicity, gender, or deprivation, but this still does not address the pre-existing problem of disadvantaged students in education. The predicted grades are comparing from previous years and not dealing with the issue of poverty and race that was already prevalent before the pandemic.

Dr Bi pointed out that the whilst the predicted grades are for this year, their impact on students’ lives are likely to be lifelong:

“The coronavirus pandemic [should] not become an additional structural barrier limiting life chances of young people,” she said. “Past inequality dynamics may be exacerbated as a result of the coronavirus pandemic for the next 20-30 years. The aim behind [the report] has been to show the long term impact.”

With GCSE and A-level results being published next month, there may not be the time or opportunity to attend to this year’s predicted grades as they should be tackled, but the conversation surrounding them has highlighted much wider pre-existing issues of inequality in our schools. The entire issue of ethnicity and poverty in the educational system needs to be addressed and the Covid-19 pandemic should be used as an opportunity to confront these problems.

Dale Anne McAulay

This article is part of the ‘Educational Inequality in Greater Manchester‘ series.

Leave a Reply