Roaa Ali, a research associate at the University of Manchester, investigates the issues around ethnic inequalities in the arts, where BAME people are underrepresented in the creation and consumption of artistic work. Guest article from The Conversation.

Have you ever been to the theatre, looked around, and thought about how predominantly white the audience is? Does the same impression come to mind when visiting museums? If it does and the answer is a resounding yes, then you’re not alone. There is a major problem in Britain’s cultural industry and it’s time we all took a hard look at why.

For years now, there has been a growing recognition of the ethnic inequalities in the creative sector. Arts Council England found it to be prevalent and persistent, particularly in theatres and museums: 12% of the workforce in national organisations in the council’s portfolio were from black and minority ethnic backgrounds, and just 5% across its major partner museums. In positions of leadership, this fell to only 9% of chief executives and 10% of artistic directors in national portfolio organisations. On executive boards at partner museums it was 3%. A recent survey showed that 92% of top British theatre leaders were white. In TV, a report from communications regulator Ofcom showed that ethnic minorities were also considerably underrepresented. It highlighted “a cultural disconnect between the people who make programmes and the millions who watch them”.

This is all despite a number of leading institutions introducing action plans and policies to improve their diversity. While Arts Council England launched the Creative Case for Diversity in 2011, to emphasise the importance and value of diversity in the arts and its significance in enriching artistic practice, leadership and audiences, leading broadcasters the BBC and Channel 4 have ramped up efforts to increase diversity. Yet change of the status quo seems to be minimal and in some cases static. The cultural sector remains steeped in ethnic inequality.

Failing strategies

There are many factors for why Britain’s cultural sector appears to be circumscribed by whiteness in ideology and practice, production and consumption. Diversity strategies seem to be failing so far, partly because “diversity” itself is a problematic term that can often dilute the problem and depoliticise the issue of racial discrimination. In the creative sector, it has morphed from an aspiration to tackle racial inequality into a drive for better business and economics – a rationale that downshifts the social impact of ethnic inequality, as film studies fellow Clive Nwonka argues.

The business case for diversity can help campaign for ethnic equality, but using it merely as a business tool can mask discriminatory practices and shift focus away from deeper issues of structural racism – for example, in embedded attitudes about art production, its consumers and its exclusivity; attitudes that enforce creative hierarchies that align with racial and class hierarchies.

Myths about high art and its audience

Many a myth still exist about cultural creation, what constitutes high or low culture, and the attitudes of ethnic minorities towards cultural participation. Commonly held opinions include, for example, that audiences from black and ethnic minorities are hard to engage – a view that ignores the lack of ethnic representation in the sector, among other realities pertaining to education and class.

In 2014, and in response to calls by actress Meera Syal for theatres to cater to Asian audiences, distinguished actor Janet Suzman was staunchly criticised for claiming that theatre was a “white invention”, that “runs in their [white people’s] DNA”. Consciously or not, statements like these contribute to a segregation of culture, and a hierarchy of cultural production.

In What is this “black” in black popular culture?, Stuart Hall articulated how the ordering of culture into high and low serves to establish cultural hegemony:

“It is an ordering of culture that opens up culture to the play of power, not an inventory of what is high versus what is low at any particular moment.”

Take grime

Ethnic and racial hierarchies get reproduced through cultural hierarchies. For example, grime music is tolerated, even celebrated, as long as it remains an ethnic genre, confined to a black experience, and so subject to hierarchical cultural positioning.

The outrage that a number of public figures (such as presenter Piers Morgan and academic Paul Stott) showed towards Stormzy when he recently affirmed that racism exists in the UK, appeared to stem from their sense that the grime artist has succeeded courtesy to whiteness, its tolerance and patronage, as a tweet from Stott suggested:

If there's one thing the British are rubbish at, it's racism. After Stormzy's dad did a runner, our welfare state helped bring him up. It may not have been perfect, but it was better than what was on offer in Ghana.

— Dr Paul Stott (@MrPaulStott) December 22, 2019

It all starts with education

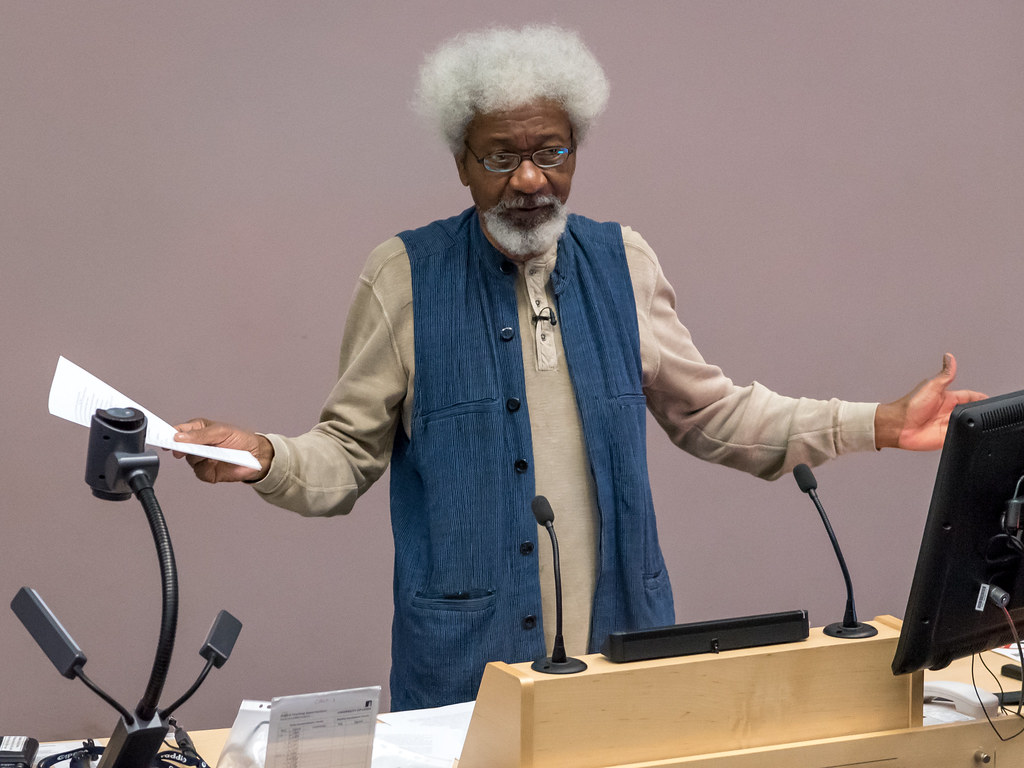

Attitudes about culture are also produced and reproduced through education. Theatre departments are probably one of the first and most essential blocs in the chain of supply for the theatre sector and cultural industry in general. Yet a predominantly white curriculum continues to be the norm in arts and theatre subjects – that is because for the most part, the canon has been constructed in the image of whiteness. As a consequence, most theatre students will study the works of Shakespeare and Bertolt Brecht, for example, but not many will consult the plays of Nigerian Nobel Laureate writer Wole Soyinka, or Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous.

Wole Soyinka : by jdco is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Wole Soyinka : by jdco is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Black and ethnic minorities are underrepresented as students, academics and authors on reading lists. As one notable report put it: although a welcoming environment, the discipline remains monocultural in terms of both its staff and curricula.

The few taught modules that focus on non-white theatres texts are offered as part of an optional stream, to add “flavour” rather as part of the core canon. This reproduces the hierarchy of knowledge with whiteness on top, and ethnic contributions valued through their proximity to whiteness. It also exoticises and exceptionalises non-white modules, created to appeal to non-white students. While these texts, and those who consume them, are both kept part of and inside the institution, they remain outside its frame of cultural influence and power.

Some scholars and activists are taking bold actions to decolonise the discipline from within. Campaigns such as Why is my curriculum so white challenge the lack of diversity in UK universities and the dominance of white eurocentric teaching materials.

Some scholars and activists are taking bold actions to decolonise the discipline from within. Campaigns such as Why is my curriculum so white challenge the lack of diversity in UK universities and the dominance of white eurocentric teaching materials.

Yet attitudes towards cultural production remain set within a frame of mind that centres whiteness as the custodian of high art. When the principal of the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama was asked about quotas as a potential way to boost diversity in 2018, his concern for the school’s standards and reputation implied that black and ethnic minorities might not possess the finesse required to meet such “standards”.

Others, such as the Black British Classical Foundation, aim to nurture interest and participation in art forms often seen as exclusionary.

It plays out in institutions

Our representations are created in cultural institutions, and it is within their daily operation, structures and processes that ethnic inequalities are either perpetuated or mitigated.

For the last two years, my colleagues and I have been researching how institutions reproduce or mitigate ethnic inequalities in cultural production. Throughout our research and interviews, the idea of exclusivity has been reiterated again and again by both majority (white) ethnic and minority ethnic staff.

Although some institutions have introduced diversity initiatives, progress seems slow and tied up to arts funding structures that are temporary and one directional – ultimately serving the institutions rather than the ethnic minorities they seek to engage. Organisations may gain funding by appealing to funders’ diversity agendas, but their engagement with ethnic minority communities and artists is rarely sustainable or lasting, leaving creatives feeling exploited and perhaps further marginalised.

Many theatres and TV production companies also aim to increase representations on stage and screen, but that really only serves as window dressing. Ultimately, creators, writers, producers, senior management and commissioners remain mostly white. The stories they tell are therefore also mostly white. The lack of diversity in the 2020 Bafta nominations is an example of a film culture that struggles to produce, represent or celebrate ethnic minorities.

Of course, class plays a major factor in perpetuating ethnic inequalities in the cultural sector, but it is also sometimes used to camouflage structural racism in its institutions. Race and class can work in tandem to marginalise ethnic minorities in cultural spaces, but racism in cultural spaces has a direct link to racism in social spaces and that has an impact on how the nation imagines itself – dictating who belongs and who doesn’t.

There is a silver lining, though. New modes of cultural production and consumption via avenues like Netflix, YouTube, and Instagram are changing traditional cultural production practices. Netflix’s large investment in original content and its subscription model means that the network is commissioning diverse content to cater for and further attract a receptive diverse audience. Such trends may yet force institutions to properly address their lack of diversity.

A cultural sector that is able to represent Britain’s diverse communities and respond to new digital means of production and distribution cannot happen without a diverse workforce, institutions that conceptualise diversity as a core strength, and funding bodies that facilitate long-term ethnic equality in the sector rather than short-lived diversity initiatives.

Roaa Ali

First published in The Conversation, 16 January 2020

Feature image: Youtube (Stormzy playing at Glastonbury 2019)

Sakib says

Chinese and Japanese art is nice. Obviously Middle Eastern architecture is amazing.