The latest estimates are that 620,000 people in Greater Manchester are living in poverty, and struggle to put food on the table. Of those, around 200,000 are children experiencing food poverty. £30 billion per year has been cut from welfare budgets since 2010. By 2020, Local councils will have lost 60% of central government funding provided for services, compared to 2010.

Food bank use is increasing, with The Trussell Trust reporting a record increase of 13% in use of its food banks in 2018 compared to 2017. Research from non-profit organisation Greater Manchester Poverty Action (GMPA) has shown that the number of emergency food providers in the region has swelled from 136 in 2017, to 203 in 2019.

Surplus food redistribution charity, Fareshare Manchester dished up over 3 million meals in and around Greater Manchester in 2018 to people in need, an increase of 50% over the previous year. Miranda Kaunang, Development Manager at FareShare Greater Manchester states on their website “… we know the need for our service has never been higher, which is shown by the unprecedented, vastly increased number of meals we provided in 2018 compared to 2017.”

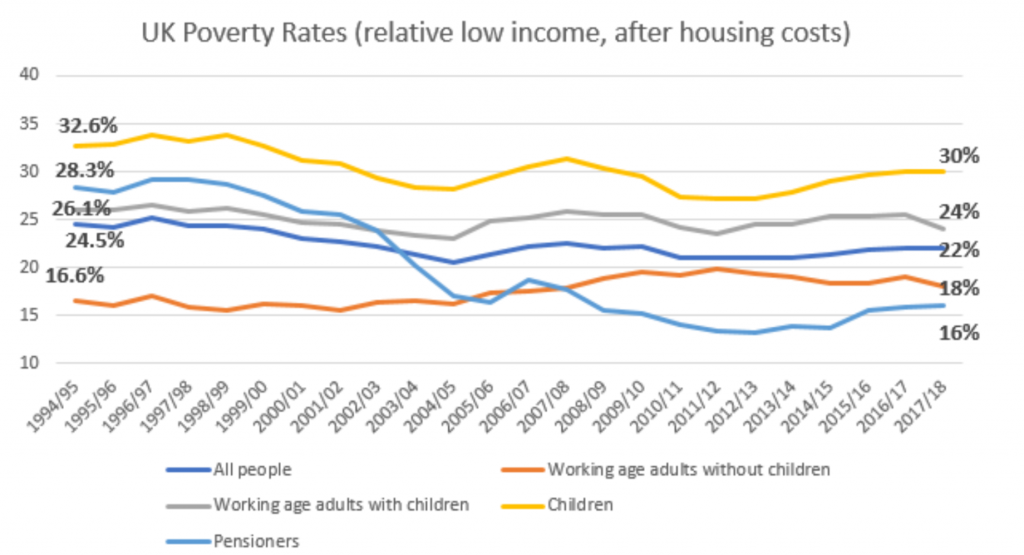

Children are disproportionately affected by poverty. UK Poverty Statistics recently released by the government showed that the number of children living in deep or ‘severe’ poverty is increasing. Of the 4.1 million children in relative poverty, 2.8 million are in ‘severe’ poverty, and under the alternative absolute poverty measure, there are 3.7 million children in poverty.

One of the difficulties with food poverty is that mostly, the costs to society are not measured, but are clearly considerable. Many existing strategies do not account for these people experiencing or at risk of food poverty; searching for food poverty or insecurity yields no results from either Manchester City Council or Greater Manchester Combined Authority websites.

It is only as recently as February this year that the government has finally listened to the many campaigners’ calls to measure food poverty, and will be incorporating a ‘national index of food insecurity’ into an established UK-wide annual survey run by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) that monitors household incomes and living standards. But with the results due to be announced publicly in 2021, who knows how much worse the situation will actually get before then?

GM Food Poverty Action Plan

The Greater Manchester Food Poverty Alliance was publicly launched in May 2018. Convened by Greater Manchester Poverty Action, it consists of over a hundred voluntary partners from the private, public and VCSE (voluntary, community and social enterprise) sectors, including many people with lived experience of food poverty. Last month the alliance released its ambitious Greater Manchester Food Poverty Action Plan.

In his foreword to the plan, GM Mayor Andy Burnham states:

“One in four parents across the country have skipped meals to make ends meet and for schoolchildren, ‘holiday hunger’ is a growing concern. We also know that access to nutritious food in sufficient quantities is crucial for good physical and mental health, for young people being able to learn and thrive at school and for success in the workplace.”

The food poverty action plan is a three-year plan which aims to reduce and prevent food poverty by building resilience, and help communities plan and adapt to the challenge of food poverty. The GM Food Poverty Alliance sees it as a necessary first step which will take a long-term commitment due to the scale and complexity of the problem.

Looking towards a more joined-up response across GM, the plan advocates for a ‘no wrong door’ approach, where an individual seeking support can be helped by whichever organisation they go to and be supported to find the help they need.

The plan will operate along the lines of the ‘place-based’ approach being implemented through the reform of Greater Manchester’s public services, with 60 ‘neighbourhoods’ across GM with approximately 50,000 residents in each. The alliance will then identify and run a pilot across four of these neighbourhoods, with the lessons learnt then to be used to develop tools to apply across all boroughs of Greater Manchester to deliver ‘meaningful food system change’ including recommended actions to help address some of the causes of poverty.

To achieve this, the plan will first look to make sure that food poverty is seen as a priority for all public services and support services, by appointing a lead for food poverty as a point of contact in each of the ten boroughs in GM. The Food Poverty Alliance will also seek funding for a full-time coordinator who will support and coordinate the actions in the plan over the next three years. In addition to the above, the alliance will raise funds and public awareness of food poverty in the city-region.

Food banks and food clubs

In terms of food support, the plan will call for an increase in the number of food clubs across GM. The alliance sees food banks as catering more for people in crisis, with food clubs being a more sustainable, longer term solution. While food banks give away parcels of mainly tinned and non-perishable items, food clubs are based on paid contributions of money and can offer higher quality fresher foodstuffs.

The alliance also believes that companies and organisations that handle food should ‘prevent unnecessary food wastage and ensure that high quality, healthy surplus food is sorted and put to good use.’

Partially following in the footsteps of measures to tackle homelessness in the region, the plan also calls for the creation of a free online food support platform for providers, similar in scope to streetsupport.net.

Food deserts and the ‘poverty premium’

Food deserts are areas that lack access to affordable healthy food. In these deprived areas, there may be no supermarkets, low rates of vehicle ownership and poor public transportation. Households are often left with poorer choice, higher costing local convenience stores as their only option. Research by GMPA has shown that people shopping at these locations could end up paying 36% more for food and everyday household items.

The Food Poverty Action Plan will identify and assess the needs of these food deserts and suggests that ‘councils may be able to use planning, grants, business rates reductions, and other tools to encourage food businesses and charities to move into these areas and improve the range of food that is on offer. The same tools, as well as regulating bus services, could help to address the poverty premium.’

Beyond food

As with many kinds of poverty, food poverty is not an isolated issue. Chronic low income, low wages and insecure wages all contribute towards the problem. The costs of food and housing have increased, whilst reform to the benefits system, the rollout of Universal Credit, and the current freeze on benefits payments all place more people into or in danger of food poverty. The removal of public services, and information about what benefits people are entitled to also constitutes a real problem that the plan looks to help tackle.

The plan will also push for welfare reform to ensure there is adequate financial support to meet households’ basic needs, whilst engaging with claimants so they understand their needs, and build support around them to reduce the use of sanctions. In efforts to tackle the increase of in-work poverty, the plan will encourage organisations and employers to become accredited Real Living Wage employers, an ideal first step to ensure that employment opportunities offer security and decent pay to employees.

As soaring housing costs are a major factor trapping people in poverty, the plan aims to push for social and affordable housing to be given a higher priority in all planning and budgeting decisions, for landlord licensing and other measures to enable higher quality housing and longer tenancies, and for temporary accommodations to all be fitted with quality cooking equipment and the basic white goods necessary for a basic standard of living.

For children and young people, the plan states that ‘schools, councils and children’s charities should work together to develop and implement a GM-wide framework for the provision of healthy and sustainable meals for children and young people, during term times and holidays, with reference to the school food standard’. The plan encourages the increase in uptake of free school meals, for schools to work with charities and local businesses to create more breakfast clubs, the coordinated provision of activities with food during school holidays, and the increased uptake of the government-funded ‘Healthy Start Voucher’ scheme; all without exposing pupils to stigma.

The plan also calls for the situation to be measured and monitored closely, so that it can be adequately prioritised and understood, giving food poverty the same scrutiny as fuel poverty, or child poverty, which are already measured. It will look to ‘work with GMCA, with support from local universities, councils and other public sector bodies, to measure food poverty across GM, and do more focused research in specific neighbourhoods.’

Initial success and long term challenges

Although in its infancy, the plan has had some early successes, with more than thirty organisations making over 70 pledges of actions or funding. For instance, Salford City Council and Salford Food Share Network have pledged to better coordinate and strengthen food support services across the city, while giving advice to other localised food support networks. The breakfast food company Kellogg’s have pledged to support 100 school breakfast clubs in GM with cash grants totalling £100,000, helping to feed at least 5000 children.

Other commitments from smaller organisations include pledges of setting up food pantries, becoming accrediting Real Living Wage employers and developing toolkits to help people and organisations tackle food poverty across GM.

Chris Bagley, of GMPA, and one of the main organisers of the plan, said:

“A lot of the people involved are passionate about tackling food poverty in GM. People can get involved and make pledges themselves, as there is no minimum pledge.”

She went on to explain that people could look through their kitchens and see if they had any unused, surplus kitchen equipment. Looking through her own kitchen she had two kettles, a coffee maker, some kitchen scales and a juicer that she was able to donate to those in need.

However, the aim of the food poverty plan is not to become a permanent part of the system; their longer-term goals are to help create an environment where individuals and organisations work together to diversify the food support system, ultimately geared towards the prevention and lifting people out of poverty permanently.

Nor does the plan look to take ownership of all of the causes of food poverty; when even Amber Rudd, Secretary of State for Work and Pensions admits that the rollout of Universal Credit has contributed to the increase in use of food banks, it’s clear there is much that could be done on a governmental scale to alleviate the problem. But while the current government seem hell-bent on imposing cruel and unnecessary cuts to services, even if they cost more to implement than the savings made, the problem of food poverty looks set to become more difficult to solve.

James KA Baker

Full information about the plan can be found here

Pledges of support for the plan can be made by emailing food@gmpovertyaction.org with PLEDGE in the subject line

Leave a Reply