When I set out to write a biography of Bill Leader, the legendary sound recordist, what I pictured myself writing about was the music, of course. Those early recordings of the Watersons, the de facto first family of English folk music. Bert Jansch’s debut album, captured on a reel-to-reel machine in Bill’s Camden flat in 1964. The vast trove of recordings he has amassed across his ninety-three years, taking in everyone from Son House to Ramblin’ Jack Elliott; Ewan MacColl to Peggy Seeger; Pentangle to Pink Floyd.

When John Ellis told me that Bill Leader worked at Salford University I filed it in the category marked unlikely occupational trivia, such as Albert Einstein worked in a patent office and Philip Glass drove a taxi. Ellis, a neighbour of Bill’s in Middleton, said Bill was a regular at the folk evening at the Oddfellows pub. I promised myself a visit. Then I landed a piece for Manchester Evening News about Bill. 800 words tops. But 800 words is inadequate to the task. Indeed 505,628 words is inadequate to the task. That’s the amount of words already expended, four volumes into a projected eight book series inspired by Bill called Sounding the Century: Bill Leader & Co. Three books have so far been published.

I set out to write a story about a folk music pioneer and found myself writing a social history. But then as we know, folk and struggle walk hand in hand. The dreams of the Young Communist League, the labours of the Workers Music Association, the longevity of Topic Records…these things are inseparable. So I found myself writing a social and cultural history, incorporating and rehabilitating first octogenarians and then septuagenarians and so on down to Baby Boomers. (That ‘& Co.’ in the title is very important.) It was something that was bigger than I was.

Born in New Jersey in 1929 to East End migrants, Bill’s parents returned to London, but the depression came with them. Their council house accommodated grandparents, aunts, cousins – all refugees from Canning Town, a nightly target for the Luftwaffe. By the time the war ended he was in Keighley, West Yorkshire, where his father’s factory had been relocated. Mother Lou was a loyal reader of the Daily Worker, Britain’s only socialist daily, and a mainstay of its annual bazaar. The paper had the best racing tipster in the business.

Dead end jobs followed, but no job could ever be as thrilling as selling records for “this bunch of nuts in London called the Workers’ Music Association.” He helped found a branch in Bradford in 1953 then volunteered at the national HQ on Bishops Bridge Road, London, becoming production manager at the Topic record club at just the moment folk music was being reclaimed as a vehicle for political struggle. With Bill recording everything in his living-room, expenses were minimal for the would-be record label.

When scrap metal merchant and aspiring label chief Nat Joseph founded Transatlantic Records, Bill was in the right place at the right time.

The title of my book series is: Sounding the Century: Bill Leader & Co. If Bill didn’t insinuate himself, Zelig-like, into every major cultural happening of the Twentieth Century, one or other of his mates did. He knew Brian Epstein before Epstein knew The Beatles. As the rep for Folkways Records one of his stops was at North End Music Stores (NEMS) in Liverpool – the shop Epstein managed for Queenie and Harry, his mum and dad.

“He cottoned onto The Beatles, which is one of the shrewdest moves any record person has done, and he cottoned onto Folkways Records too,” says Bill. The sweat ran off the walls at the Cavern Club and the toilets were ankle-deep in urine. “It was an interesting place!”

It was a crossroads of musical frontier and societal change, which is what I’ve tried to highlight in my account: in volume 4 [Time Immoral: 1959-1966] the sedate world of folk music rocked by gangsterism; in volume 5 [And Now It Is So Strange 1965-1968] an exploration of culture and decay; in volume 7 [A Messy Garden, If It Is a Garden: 1969-1978] an account of Bill’s years helming the Trailer and Leader labels.

Because Ramblin’ Jack Elliot (right) didn’t have a work permit, a plan was hatched to record the cowboy singer – and keen yachtsman – outside of territorial waters, which at the time was a modest three miles. Thus, Topic’s 1958 ten-inch LP, Jack Takes the Floor, was recorded on board The Magnet, a yacht berthed at Cowes, Isle of Wight. They didn’t feel the need to go the whole three miles out. It was a monumental session, the out-takes furnishing material for two further CDs in 2004. Photo: Brian Shuel

It’s a personal opinion, but a portrait of Britain in sound recordings (if Bill’s career doesn’t quite manage an unbroken century of work it comes darn close) can restore to you a sense of humanity that was always, until recently, to be found in the national spirit. Bill’s own story is the story of anyone who has been buffeted by the impersonal forces of history. As someone blessed with a long life, Bill has been buffeted by more than most, from the traumas of the Second World War to the collective calamity of 2020, the plague year.

And that’s why I say my biography of Bill Leader amounts to a social history of the 20th Century.

Bill is Everyman.

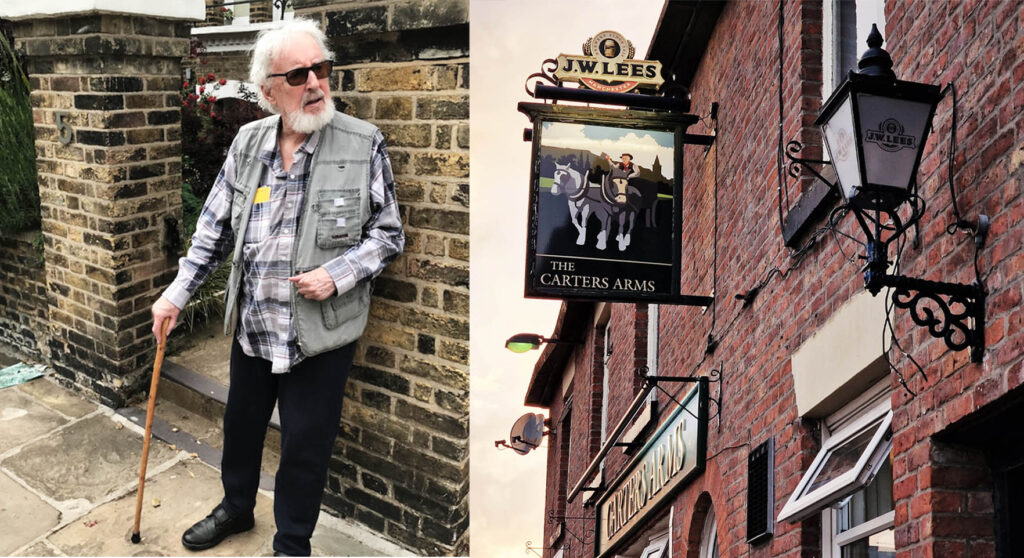

John Ellis: “I was teaching in the music department at Salford university, this was the early 2000’s, and at the same time Bill was teaching the sound engineering course, so we’d record the students. About six or seven years later I set up a recording studio in Middleton, and I was going down to the ‘Oddies‘ folk night – folk being a bit out of my field. But I wanted to record them, I thought it would be interesting to take some microphones down as a project, and I was reading (top US record producer) Joe Boyd’s autobiography, White Bicycles. Part way through there’s a section about how Bill was one of the main influences in his life. And I thought, he’s literally on the same street, so I got him down to the Middleton session. It turned out he’d recorded one of the musicians, John Howarth of the Oldham Tinkers, for the Deep Lancashire album in the 60s – he hired a room at Manchester University and had them all traipse through one by one – and never met him since.”

“We recorded two albums with the guys from Oddies, an album called Black Lung with Rioghnach Connolly [pictured] which I know she’s particularly attached to, one with George Borowski, and a set of Jacques Brel songs by a band called Dead Belgian from Liverpool. I was very, very lucky. To learn from Bill… his approach at Topic Records was coming from a Communist background, basically. It was about being as invisible as possible and recording what was out there. Very utilitarian. Just a tape machine and one or two mics. That utilitarian idea of what it sounds like in the room. How subtle movements in mic placement make such a difference. And his spirit around the place… very kind, very gentle. Generous. He’s how to grow old gracefully.”

Six key Bill Leader recordings

Second Shift – Ewan MacColl (1958)

Important because it proved the existence of industrial folk song. If an industry was song-less MacColl would pen one himself, becoming variously a road builder (‘The Song of the Iron Road’) and an electrician (‘The Fitter’s Song’), and elsewhere a miner (‘The Big Hewer’), fisherman (‘Shoals of Herring’) and lorry driver (‘Champion at Keepin’ ‘em Rolling’).

Who’s going to shoe your pretty little foot? Who’s going to glove your hand? – Tom Paley and Peggy Seeger (1964)

Two US urban hillbillies adrift in the UK. Three duets, seven Peggy solos, five solo Tom… his country picking gelling with her dexterity on the banjo. Freed from MacColl’s ironclad asperity, Seeger seems almost girlish.

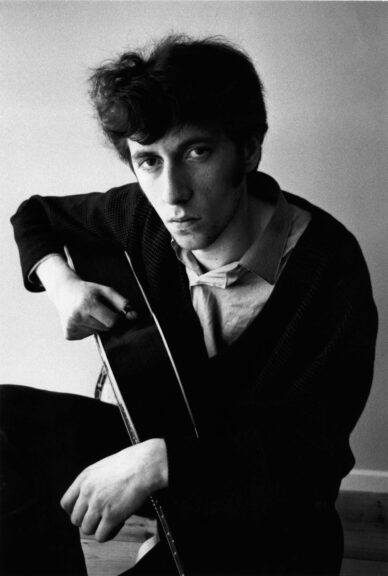

Jack Orion – Bert Jansch (1966)

Bert’s fourth solo album reunited Bert with Bill and introduced traditional songs to Bert’s repertoire, which has an invigorating effect. Bert hardly sounds doleful at all and the ferocity of his guitar playing is striking. It’s curious how an ancient song like ’Nottamun Town’ provides an apt commentary on the chaotic personal life of the singer.

Frost and Fire – The Watersons (1965)

Topic chief Bert Lloyd heard the Watersons singing ceremonial songs and suggested a whole album of the same, augmenting the popular ‘Holly Bears a Berry’ with more esoteric fare. It was also Lloyd’s idea to structure the album around the calendar. The resulting album introduced a generation to ritual songs of their own heritage.

Deep Lancashire – Various (1968)

The album which introduced Lancastrian humour to the wider world, along with the likes of Mike Harding, the Oldham Tinkers and Harvey Kershaw. Dialect poetry, playground songs, industrial ballads… Deep Lancashire created a groundswell of regional pride that far transcended the folk scene. It was Topic’s biggest seller before Nic Jones’s Penguin Eggs came along.

The Noah’s Ark Trap – Nic Jones (1977)

All the qualities that made Penguin Eggs so distinctive – free-flowing songs which sustain incredible excitement, voice and guitar locked in exhilaration – are to be found in even greater abundance in this 1977 album for Bill’s own Trailer label.

Sounding The Century: Bill Leader & Co (Vols 1-3) by Mike Butler are available from Troubadour Publishing here

Folk night at The Carters Arms is every Monday from 8.30pm: 610 Manchester Rd, Rhodes, Middleton M24 4PW. Tel: 07415 987913

Folks, folkies and all community-minded Mancunians! The Meteor is a co-operative on a mission to democratise Manchester media, and it is available to YOU! To find out more – click here.

Sign up to The Meteor mailing list – click here.

Feature image: Bill Leader and Nathan Joseph at Olympic Studio (Brian Shuel)

Vincent J. Doherty says

Extraordinary and hugely enjoyable piece of social and folk music history.