Are the people of Manchester getting good value in the deals Manchester City Council strikes with developers? A report from geographers at the Universities of Manchester and Sheffield looks at the privitisation of public land in the city and asks this question.

The council insist they are providing good value, but a lack of publicly available data, means the researchers are unable to put together a comprehensive picture of land privitisation in Manchester and are calling for a Land Commission.

The rapid expansion of new buildings and renovations in the city creating vibrant, fashionable new neighbourhoods denotes prosperity and forward movement. But many housing campaigners are increasingly worried that this prosperity is limited to the lucky few and the new build flats are safety deposit boxes and the preserve of the affluent. Manchester council continues to sell off large amounts of publicly owned land in property deals with developers, but who is benefitting from these deals?

This is what geographers Dr Tom Gillespie at the University of Manchester and Dr Jon Silver at the University of Sheffield are trying to find out. Who Owns the City is their new paper on the privatisation of public land in Manchester. Citing the lack of social and affordable housing in Manchester the report states, “There are growing concerns amongst researchers, journalists and civil society groups that public land has been allocated to private developers to build unaffordable apartments.” Part of the concern is housing is being built in response to a speculative market rather than to meet local market needs, and public land has been sold off to do so.

In this report, Gillespie and Silver “aim to establish whether public land ownership and use is transparent, whether public land disposals have been good value for the public, and what type of city is being built using public resources.”

Missing data

To get a clearer picture of the economic reality behind the new developments across the city, Gillespie and Silver turned to land disposal data tables from the council and title deeds from the UK Land Registry. But these only allowed them to assemble a partial view of development.

To fill in the gaps the researchers submitted Freedom of Information requests to MCC, asking for details of council-owned land or property in central wards that had been sold or leased between 1999-2019.

But Gillespie and Silver write, “We became aware that the datasets we were given in response to our FOI requests appear to be incomplete, and that various sites that were leased by the council to private developers were not included.” As an example, they cite the land incorporating the Cardroom Estate in Ancoats as missing, “It is not clear why these sites were not included,” say the researchers.

In 1982, MCC owned 57% of land in Manchester. Without complete data, Gillespie and Silver are unable to report how much land the council owns today. When the Meteor asked MCC how much land the council owns, they responded:

“We do not hold that information. While we have full detail on our land holdings we cannot say what percentage of the total area of the city they constitute.”

Regarding why the FOI data was incomplete, they said:

“In answering these FOI requests, the Council will have reviewed its digital records relating to land transactions throughout the 20-year period specified and answered to the best of our knowledge, having regard to the information available and the time constraints.”

In the report Gillespie and Silver write, “the first issue is the lack of transparency around public land ownership and use in Manchester.” Not only did the council data not contain all sites, it didn’t specify who land was sold to for the sites that were included. For this, the researchers had to access title deeds from the UK Land Registry for £3 per property. “In our view,” the researchers say, “information on how public land is being allocated and on what terms should be freely and easily accessible to the public.”

How much rental income does the council get?

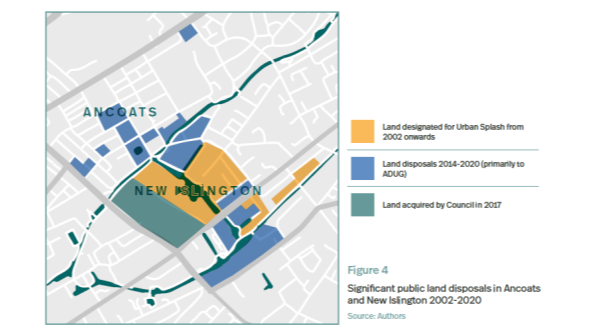

Although incomplete, the FOI’s returned enough data to allow Gillespie and Silver to take a closer look at specific wards. For this paper, they chose to zero in on the Piccadilly and Ancoats & Beswick wards in central Manchester. This is where, according to previous research by Silver on housing financialisation in Manchester, a large number of apartments have been built without any on-site affordable housing and poor provision of Section 106 agreements that provide money from the developer towards infrastructure improvements in the area.

In Piccadilly and Ancoats & Beswick, 28 sites were identified where residential development had already occurred or was taking place. In response to another FOI request, the council confirmed they don’t receive any rental income for the 28 sites, despite some of the leasehold agreements extending up to 999 years. This confirms the findings of a 2019 Sunday Times investigation which revealed that the council receives none of the rental income from Manchester Life’s property portfolio, which includes developments in Ancoats and Beswick. This is the joint-venture the council formed with the Abu Dhabi United Group (ADUG), a private equity company owned by Mansour bin Zayad Al Nahyan, Deputy Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates. Manchester Life was set up a few years after Mansour bought Manchester City Football Club. Its portfolio boasts four blocks of flats for rent (Cotton Field Wharf, Sawmill Court, Smith’s Yard, Weaver’s Quay) and three buildings with flats for sale (Murray’s Mills, New Little Mill, One Vesta Street).

Cotton Field Wharf is likely one of the most familiar of Manchester Life’s portfolio. These are the black brick apartment buildings for rent alongside New Islington Marina, a radically transformed neighbourhood. Anyone who has spent time in the area will know it is teeming with life, especially on a hot, sunny day.

The report recounts how Manchester Life was established in 2014 “so that ADUG could invest in urban development in Manchester via the Jersey-based off-shore company Loom Holdings Ltd.” The report explains, “Public land for Manchester Life developments is typically transferred to ADUG via Loom Holdings on long leases of up to 999 years.” In other words, public land is transferred to an overseas developer ultimately registered in an offshore tax haven to build luxury flats the council receives no rental income from.

Cotton Field Wharf alongside New Islington Marina. Image. Google Maps

Manchester Life’s website explains that being domiciled in Jersey “provides certain advantages for the shareholder in the event shares are sold in one of the rental developments, and is a common structure for overseas investors making U.K. investments.” It seems fair to ask, who is benefiting most from these arrangements?

According to the 2019 Sunday Times investigation, the council said that while it doesn’t receive any rental income from Manchester Life’s property portfolio, it stands to make money from “longer-term profit sharing arrangements.” Gillespie and Silver were unable to find any publicly available information on whether the council has received income from the sale of Manchester Life properties.

The council confirmed to the Meteor it doesn’t receive any rental income from Manchester Life’s property portfolio, nor does it have any ownership interests in the rental buildings. “However,” they say, “as joint venture partners in Manchester Life and in accordance with the commercial arrangements, where profits or surplus are realised the Council is entitled to a share of the profits/ surplus.” They note that “any service charges are reinvested in the ongoing management and maintenance of the area.”

The council also point out that in their agreement with ADUG to develop sites in the Eastern Development Area, “the Council was not required to provide any funding for Manchester Life as this was to be the responsibility of ADUG.” They say the Eastern Development Area is envisioned to deploy “up to £1bn by ADUG, the Council and other investors over a 10-year period.”

Regarding their joint-venture with ADUG, the council say, “Manchester Life as an investor, and platform for regeneration and community development is a long-term commitment to Manchester and has delivered a thriving neighbourhood and brought confidence back to a community. Ancoats and New Islington would not be what it is today without Manchester Life.”

Does the public get value for money when public land is sold?

According to the report, Manchester Life is “the single biggest beneficiary of public land disposals and the single biggest developer of residential units in Ancoats and New Islington.” It looks to gain further from the development of 10.5 acre former Central Retail Park, which has been at the heart of a heated local campaign. While the council plan to develop the site into an office park with ADUG, local campaign group Trees Not Cars are calling for it to be turned into a community green with affordable housing. Trees Not Cars won a court case this past February against the council, stopping them from using the site as a temporary car park.

The site drew the attention of Gillespie and Silver because of the amount the council paid for it. While they sold the site of nearby New Islington Green for £528,000 per acre, they bought Central Retail Park for £3.5 million per acre. “Although we recognise land prices can vary from site to site,” write the researchers, “these transactions suggest that the Council could be paying over nine times more than it is receiving in income for land in the same neighbourhood.”

A local resident opposing the development called New Islington Green a “sweetheart deal with developers” at a planning committee meeting that approved the proposal.

When we approached the council about the difference in price they were unable to provide a response at the time of publishing. The Meteor will provide an update when a comment is available.

Apart from Central Retail Park, the report draws attention to other notable public land disposals in central Manchester. One example is the ‘Oxygen’ tower, a £82million 32-storey apartment block on Store Street in Piccadilly ward. “Home to 12 luxury townhouses at ground level and 369 apartments,” the tower’s website says, “Oxygen sets a new benchmark for what luxury living should mean in Manchester.” It goes on to say the tower is “on the doorstep of Ancoats – a neighbourhood voted as one of the most cosmopolitan in the world.”

Oxygen is one of the developments being sold off plan to overseas investors in places like Hong Kong as I discovered in previous reporting. This is further supported by the title deed from the Land Registry which The Meteor has seen.

While many of the flats in Oxygen appear to be sold to overseas investors, the council leased the land to the developer for £1 (one pound) for 960 years. The development includes no affordable or social housing provision. Gillespie and Silver write, “This case raises questions about why the Council appear to have transferred public land to a developer for £1 so that they can build a scheme without affordable housing provision on-site.” They estimate, using current rental prices, that the developer is set to make £4.77 billion in rental income over the course of the 960-year lease.

Oxygen isn’t the only development where public land was leased by the council for £1. Another example is the new Hampton by Hilton Hotel, the researchers state, “Demand for hotels has been growing in Manchester for a number of years, and it is understandable that the Council wants to support the growth of this sector. However, in our view this disposal of (some or all) of the land for £1 to a corporation with estimated assets of $14 billion raises further questions about how the Council values its land assets.”

When The Meteor asked the council about land disposals for £1, the leader of the council, Sir Richard Leese said:

“The amount of money we can realise for a site for depends to a large extent on the exact legal interest the council has in it. This land can have little to no actual market value for a variety of reasons. For example, with a number of the development sites we have disposed of there was already a pre-existing contractual obligation to grant long leases to a particular developer when we acquired the land. In other cases, there were already long leasehold arrangements and the ‘disposal’ of the site was actually just an extension of the lease, known as a re-gearing.

“In other cases, as with the Oxygen Tower site, the Council acquires the land from the developer for a nominal sum and then leases it back for the same amount, to remove technical legal obstacles which could discourage development. This is part of the Council’s important role in assembling sites for regeneration schemes, especially for housing on brownfield land. Far from selling the land for next to nothing, the City Council acquired the freehold for next to nothing.

“In other instances the benefits of the development being brought forward, for example where it is for the delivery of affordable housing, would not be realised if we demanded full market value for the land involved because it simply wouldn’t go ahead. In such cases it is justified to dispose of land at less than its market value.

“Individual transactions are not considered in isolation but in the context of how they support the wider development framework for the area and contribute to the overall success of the city.”

Calls for a Land Commission

Who Owns the City is based on partial data. It draws attention to concerning examples of developments where it’s not clear whether the council and the people of Manchester are getting their fair share of deals with developers. The concern from housing activists is that they are contributing to growing inequality in the city. “In our view,” write Gillespie and Silver, “greater transparency and accountability over public land ownership and use will enable a much-needed public debate about the future of urban planning and land use in the city.”

They are calling for a Land Commission, similar to the one recently launched in Liverpool. It includes representatives of the public, private and voluntary sectors and academia. According to Liverpool’s Metro Mayor Steve Rotherham, the aim is to develop “radical recommendations for how we can make the best use of publicly-owned land to make this the fairest and most socially inclusive city region in the country.” Andy Burnham pledged to establish such a Land Commission in his manifesto. Gillespie and Silver are calling for Burnham to make good on his pledge by the end of this year.

When asked whether the council’s Executive will support calls for a Land Commission, they said:

“The 2014 Greater Manchester devolution agreement established a land commission intended to cover all publicly owned land and to be jointly chaired by a Minister and the GM Mayor. It had one meeting. We would of course be interested in any proposal that led to a more joined up approach to using publicly-owned land for regeneration purposes, but decisions on Council-owned land would still fall to the Council and we don’t see how a land commission would be any more transparent than is already the case.”

Who Owns the City is the initial report of an on-going project. We asked Dr Silver what the next phase will look like.

“In the next stage of the research we hope to work to establish an interactive map that allows the public and decision makers such as councillors a tool to help them understand how public land has been disposed of at a ward level over the last two decades, and what value was captured by the Council, as well as what happened to the land.

“The aim is to help establish better public knowledge about this important issue that affects us all, and to inform future debate about the public land that is still held by the Council.

“Given we are in a Climate Emergency and housing crisis what we do with future public land is vital to the efforts by the city to address these pressing problems.”

What impact will this work have? After Silver published his 2018 report on housing financialisation in Manchester, which was reported on by The Meteor and other media outlets, the council made viability assessments (documenting financial arguments of developers to allow them not to build affordable housing) publicly available. Since then the amount of Section 106 contributions in developments has also increased, as has a small amount of on-site affordable housing in Swan House.

With more data, a fuller picture of who owns Manchester will be developed. But that can only happen once complete data on land privitisation is made publicly available.

To read the report Who Owns the City – click here

The Meteor is a media co-operative, if you would like to find out more about joining and supporting our work – click here

Sign up to The Meteor mailing list – click here

Featured image: Filip Patock

John Byrne's Ghost says

I am assuming that the developers are so grateful to the Council for their bargain land – and in turn the Council for their ‘development’ – that they will be rushing to remedy any post-Grenville fire safety issues (if they have not done so already)?