Schools need to urgently prioritise anti-racism according to a report titled Race and Racism in English Secondary Schools, based on interviews with 24 secondary school teachers across Greater Manchester.

Dr Remi Joseph-Salisbury, the author of the report, argues that the school system operates on a classist logic, producing inequality for many groups of students, but that race, and racism, continue to be a defining feature of the school system.

Members of the Greater Manchester BAME network agreed, during a Q&A with The Meteor. They pointed out that many groups are marginalised but in a society based on white privilege, institutional attitudes towards colour also transfer to the playground. Many identities overlap, which is very relevant when you consider that almost half of UK Black African Caribbean households were found to be in poverty, compared to one in five white families, according to the report Measuring Poverty 2020 by the Social Metrics Commission.

The Race and Racism in English Secondary Schools report, published by race equality think-tank Runnymede, focuses on how schools can tackle racism and racial inequality. The report concentrates on the schoolteacher workforce, curricula, police, and school policies rather than educational attainment and suggests changes to work towards racial equality.

Schoolteacher workforce – diversity and racial literacy

It was noted in the report that a diverse teaching force would benefit students of all races to help combat negative stereotypes.

Currently 8% of teachers, and only 3% of headteachers, come from ethnic minority backgrounds. Commenting on the lack of diversity, especially in senior and management positions, one teacher is quoted as saying, “what is important is that pupils have role models to aspire to.”

The report points out that there is and will continue to be a white majority teaching staff for a while, arguing that “it is vital that anti-racism is seen as the job of everybody.” One BME teacher stated that “training of white teachers is also very important as well.”

Racial literacy therefore needs to be placed at the centre of teachers’ role and teacher training. In the report, racial literacy is defined as the capacity of teachers to understand the ways in which race and racism works in society, and to have the skills, knowledge and confidence to implement that understanding in teaching practice.

Vik Chechi, science teacher and organiser of the Northwest Black member forum for the National Educational Union, says that teachers have asked for training in many areas, including anti-racism training, but lack of funding and emphasis on exam results leave little resources in this area.

Curriculum

Dr Joseph-Salisbury noted that the curriculum “reflects the way the country sees itself and it has profound implications for our society in the way we interact with each other, and the way people understand their own importance of British people.” One teacher quoted in the report describes the curriculum as “too white and too narrow.”

Whilst diversity should be across the curriculum and integrated across all subjects, it was found that focus on examinations restricts time and content, with the curriculum, as well as textbooks and resources, being tied to exam boards. One teacher noted that, “the people on exam boards are going to be overwhelmingly white because they come from that very high academic position” and research shows that both exam regulator Ofqual and school watchdog Ofsted had all white board members.

The report suggests that beyond seeking a more diverse curriculum, we should be working towards one that is anti-racist, and pro-active in implementing this programme. It should not just include how individual acts of racism are wrong but could also seek to engage white students with “considerations of white privilege, power and complicity, in order to better understand and question their position in contemporary society,” while BME students could engage with content “that prepares them for life in a racist society.”

Members of the GM BAME Network in a discussion with The Meteor pointed out that the current curriculum “talks about slavery in a demeaning way…does not address world history…and also ignores, not just Black history, but South Asian history, and does not address issues such as the Pakistan India partition. The whole curriculum needs to change and it needs to start in primary school.”

Police in Schools

A school is a place of sanctuary for many already marginalised students and Vik Chechi, NEU, strongly believes that police should not be in schools. He commented that Andy Burnham’s plan to expand the number of police officers in schools would “impact black students that are already over policed, already face surveillance, already get stopped and searched.” A survey by the NEU found that two thirds of the 120 teachers of all races that were asked did not want police in schools.

Dr Joseph-Salisbury explained that supporters of police in schools feel that students will be embraced by “the nicer face of police” but it has been shown that “police revert to oppressive forms of policing….as it is embedded into policing.” He maintains that “police need to stop institutional racism in the force first” and “placing vulnerable students at risk into the institutional racist school and police systems, bringing the two together, could have dangerous consequences”.

Remi posed the question, “if we want police to play pastoral roles, then why not use those kind of people?” and noted that policing in schools has not been very effective in North America.

He also found that there appears to be connections between the placement of police in schools with a radicalised moral panic around terror and Islam under the Prevent programme. This leads to police in schools being tasked with preventing extremism, resulting in racialised surveillance of students from these backgrounds.

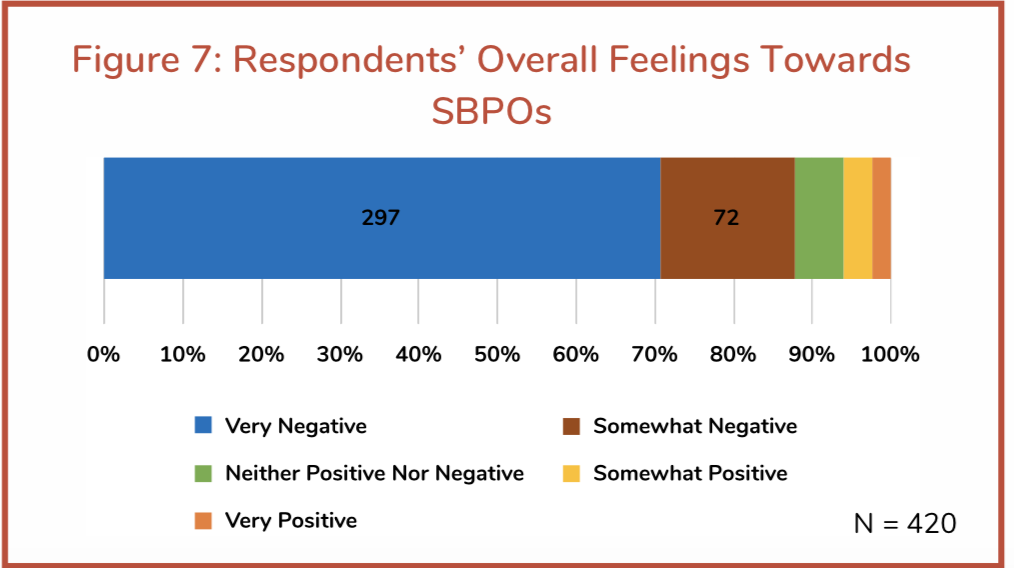

In the report, Decriminalise the Classroom-A Community Response to Police in Greater Manchester’s Schools, the 554 young people, teachers, parents, and community members surveyed overwhelmingly had a negative response to School Based Police Officers (SBPO).

School Policies

School policy, in terms of interpersonal racism between students, was clear in some schools, but teachers in the report revealed that many schools had policies that were unclear or unknown. Teachers in schools with clear policies found that they felt supported when dealing with racism, but felt that zero-tolerance rules could be restrictive and unhelpful.

Black students are more likely to be excluded in school and placed in the lower set, according to Chechi, from the NEU. He added that Black students are prone to be caught up in zero-tolerance policies with issues about hair.

Rules about school uniforms and hair follow a concept of what is considered acceptable and the school’s definition of ‘neat and tidy’, according to teachers in the study, and many were aware of and concerned about these issues.

Dr Joseph-Salisbury also noted that hair and uniform policies that are based on what some people think as professional are “all culturally and racially prescribed”. He gave an example that “dreadlocks in Rastafari culture are seen as a symbol of discipline and commitment….[it takes] dedication to tame your hair in that way…it is a form of dedication and discipline which is not the way that schools see it.”

He also told The Meteor that some school uniform policies are so strict that “if people saw this kind of stuff on a dystopian Netflix documentary [they would think] ‘that is crazy’, but it’s just so normalised…these constraints on young peoples’ self-expression at an age where people really want to express themselves.”

Kids of Colour, a platform for young people of colour, made a public statement in June outlining problems at college in Greater Manchester, in regards to their treatment of black students. It describes problems with policies such as discriminate punishment with respect to things such as hair, students’ inability to complain, in-school policing, and exclusions. The college has since sent out a communication to parents and carers expressing their commitment to “ensuring all students are treated without discrimination” and are planning to review their curriculum in light of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Excluding can be a way to create the kind of environment that you want in your school quite quickly,” according to Dr Joseph-Salisbury.

“In a perfect world I think we should have prevention not intervention….behaviour needs to be addressed in more effective ways…some schools have no exclusions and they invest in supporting students one to one.”

The road to anti-racist education

Vik Chechi, from NEU, sums the current situation up by pointing out that the cuts in education have created less resources, increased class sizes, and a teacher recruitment crisis, but on top of this, “in schools [institutionalised racism] is reflected by Black students being more likely to be excluded, put in a lower set in school or in conflict with zero tolerance policies on things such as natural African hairstyles”.

Dr Joseph-Salisbury believes that “investment needs to be made in schools” to bring about an increase in teacher numbers, a reduction of teacher workloads, and a reversal of cuts in education which will lead to the environment necessary to bring about anti-racist changes in education.

This environment would include teacher training that includes racial literacy as part of continued professional development, along with efforts to increase BAME teacher numbers. An anti-racist curriculum should be embedded across the curriculum with a review of issues of interlocking issues of exam specifications, textbooks, school resources and teachers’ racial literacy levels.

Separation between education and criminal justice should be safeguarded by not normalising police in schools and using the funds designated for police to bring in experts to help students with problems. School policies should be reviewed by anti-racist organisations to help identify racist policies.

Dr Joseph-Salisbury told The Meteor:

“Society needs to reimagine the importance it places on teaching…it should be seen as one of the most important jobs in our society and that’s a fundamental problem that needs to be tackled.

“From there then we can have a conversation about race and class…Teachers should understand racial literacy as a constant journey, and they should be given the time, support and resources to pursue that journey.

“It should be part of continued professional development within schools…and part of a whole-school institutionalised approach.”

Feature image: India Joseph

To read more articles in the Educational Inequality in Greater Manchester series – click here

Stephen PENNELLS says

Hmmm…. “Back in the day” I was on the staff of Ducie (Central) High School- the first Manch. school to be sold out to become an academy. (I have nothing to say about Manchester Academy, never having been there beyond dropping something off for a friend at the entrance.)

We were closed, but NEVER declared by Ofsted to be a “Failing school”. We had low, low levels of acad. attainment, but we also had deliberate practices and teaching to promote esteem of our community. We had support from (and supported) local community education, in partic. Berry Edwards/Nana Bonsu. We also had positive roll modelling from the likes of Paul Wilson-Eme, Devon Brown, Andrew Brown, et al., who went beyond the required to reach the parts others failed to reach.

Beyond this Manchester LEA (when we had such a thing) supported peripatetic Steel Band and Tabla teaching in the school and we had advisors and projects that were antiracist.

So much of this withered under the quasi-privatisation ethos of devolving spending to schools and the pressure to “deliver” for an exam system that focused on “British”.

I wonder where all this is now.